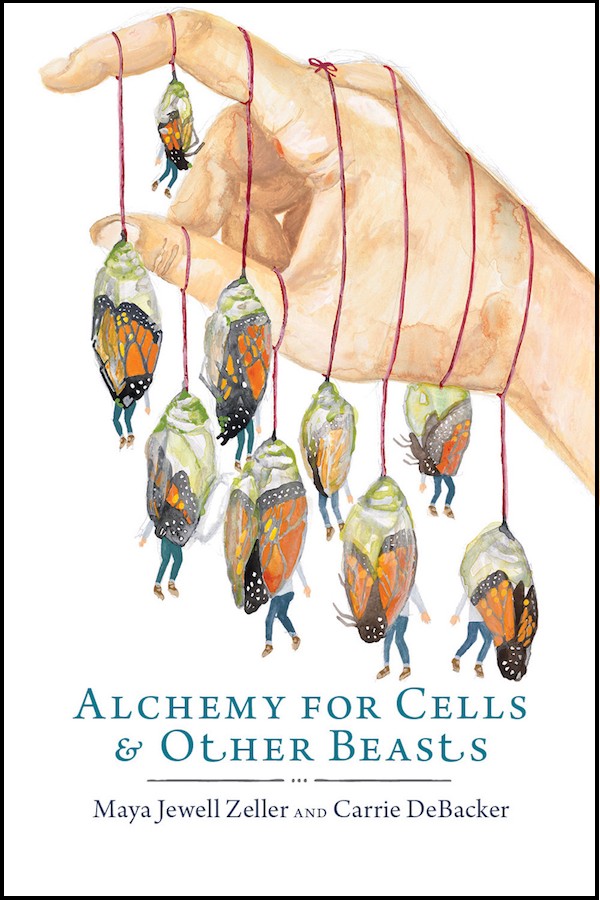

Alchemy for Cells and Other Beasts (Entre Ríos Books, 2017) by Maya Jewell Zeller and Carrie DeBacker

Halfway through Maya Jewell Zeller and Carrie DeBacker’s luminous and revelatory Alchemy for Cells and Other Beasts, I looked up “alchemy” in Merriam-Webster. It’s a word I thought I knew, but it turns out I had only a vague idea of its meaning. Alchemy means both “the medieval chemical science and speculative philosophy whose aims were the transmutation of the base metals into gold” and “the discovery of a universal cure for diseases”; more broadly, “a great or magic power of transmutation.”

The collection’s title is beautifully apt. Zeller’s poems and DeBacker’s paintings tap into a power that might seem magical to our everyday logical minds, inviting us to consider the ways in which that power is already present in the worlds around and within us. At the same time, the paintings and poems conjure more: more transformation, more recognition of our interrelatedness. There’s alchemy, or the desire for it, in the longing the speaker feels to heal disease suffered by a particular human body, a longing especially present in the three poems titled “little spell with chest x-ray.” There’s the desire for alchemy for the wider natural world—to heal and transform in the midst of political and climate-related crisis. And there’s the recognition that these experiences, these desires, are inseparable, one and the same.

The rest of the book’s title also does important work. The invocation of “cells and other beasts” points inward and outward, toward the cells of the particular human speaker facing illness and depression, and toward the myriad others inhabiting the book. In the world of Alchemy for Cells and Other Beasts – which is our world – the sense of inward and outward breaks down as the poems and paintings rearrange our understanding. “if you watch in slow motion / the flecked kestrel / on YouTube,” Zeller asserts in “little spell for kestrel hovering / for x-ray & mothering,” “you’ll watch your own lungs fanning out against the sun.”

How open this book is: permeable, inviting. “I said, sure, America, come on in,” Zeller’s narrator offers at the end of the book’s first poem, “Upon Finding Out They Were Wrong, the Scientists Had a Good Long Chuckle.” The poems and paintings open to the wide world of beings and things – paper airplanes, pomegranates, roller derbies – as well as to the wide emotional and spiritual realms within each of us, with a radical even-handedness. Zeller and DeBacker invite us to consider how things might look, might feel, were we to recognize how deeply we are connected: with each other, with milkweed, finches, history. And while the poems never oversimplify this connectedness, or take it lightly, they call us to open, too, as the speaker is opened in “Dirge for a Temporary God”:

& when I was ripped apart

by creating other winged beings

with invisible wings,

it became possible to admit things

& still it took years & years

to imagine what I could open into

if I’d found these seams earlier –

when I was a girl, I tore my foot

on a ripper

in a carpet

Oh

my mother said

you found it

thank you

now I can make those floral pants

you really wanted

& my blood was everywhere, the wound

stardust flailing into the form of petals, of waves (34-51)

Here is the body, both a particular female body and a body that morphs into and meshes with other bodies as it experiences illness, childbirth, depression, love, memory; the body as it overlaps and communes with children, butterflies, and boars, as it is born and broken down into stardust, petals, and waves.

At first, I felt tempted to call the book “surreal,” given the whale heads and hammers perched on top of human bodies in DeBacker’s glowing watercolors, and given the way Zeller turns her careful and pointed attention equally toward the everyday and the dreamlike. Take, for example, these lines from “The Waiting,” which fuse the recognizable and the deeply, radiantly strange:

I put on my black mask

and walked into the mountain. I pushed right through the stone.

I wore a necklace of furred insects, emerged in a forest,

stepped into a boat, I rocked inside with seismic proportions.

I drew a knife from my belly, plundered the lake. I put on my wolf head,

my girl arms, my quiver of bodies.

Though I wanted to use the word, I wondered: is it correct to call this poem – to call any of these poems or paintings – surreal? It seems to me now that to the poet and artist, this blurring of people and insects and fish and stone is, instead of more or other than, simply real. This is how things are, the poems seem to say. Listen. Look.

Other descriptive words that came to mind when I was planning this review also felt off. Zeller’s poems are both deeply personal and adamantly political and global: so quirkily, movingly, newly so that none of those words seems right. The poems consider the physical world and the invisible interior, but move so delicately between the two that the lines between them seem to dissolve, if they ever really existed. Here’s a rich example from “Spell for transcendence / for conjuring finches”:

here in the suburbs / park

swings rusted for extra months / puddles in their saggy

middles / this has nothing to do with my uterus / it

is the longest winter since that one long before this

winter / so long we cannot remember the feel of the

earth then /everything it is was the world we barely

remember /

& I start to whisper things like reuptake

inhibitor / not knowing the meaning of my own chemicals

/ I can barely function / I like to mouth things like

monoamine transporter / picturing them floating between

synapses / like unpollutable balloons /

I say remember when

& “Ray LaMontagne” / You say I am “being nostalgic” / say

I am “being hyperbolic” / as if hyperbolic is not the new

curved beak / meant for prying insects from bark / (4-19)

Brain chemistry, extreme weather, memory, relationship, and birds are folded seamlessly into these lines: no way to separate one from another. In resisting dichotomies and binaries, the poems aim to upend what we think we know about where “we” stop and “everything else” begins.

Alchemy for Cells and Other Beasts balances wildness – in the form of associative leaps and startling correlations – with steadying order, present in the book’s recurring images, titles, and forms. Many of DeBacker’s paintings depict human bodies with non-human heads (bones, knives, hummingbirds), and the artist often repeats images, with slight variations, within each painting. A series of “little spells” – many of which are formatted as prose poems employing back slashes to separate phrases – anchors the written text, providing an emotional and verbal spine, reminding us that the book, too, is a type of body.

(Side note: I love how much I learned, reading this book. “Chert,” for example, is “a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock,” and to “knap” is “to break with a quick blow” – both of these from the wonderfully titled “i need large electric oven roaster, around 20 qt. If you have one taking up space, get back to me. I’m using it to heat alibates chert for knapping.”)

“The world is such a place of light, had we eyes,” writes Mary Rose O’Reilley in her collection of essays, The Love of Impermanent Things. Zeller’s poems and DeBacker’s artwork have such eyes, and they beckon us to a new and potentially healing, alchemical way of seeing: they look beyond received ideas of “human” and “animal,” “inner” and “outer,” into the heart of our connectedness, and they aim to startle and dazzle us into doing the same.