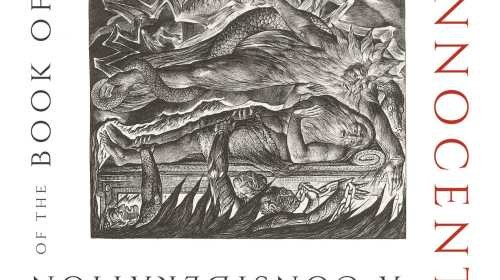

Diane Glancy’s publication career spans three decades and includes dozens of books and articles. Her works span poetry, history, plays, films, short stories, and essays. Ms. Glancy tells American stories. “American” here, in the oldest sense, in which the word would not apply as well as “Turtle Islandian” or “Lakota,” “Sioux,” or “Cherokee” stories. Many of her works weave in themes of Native American history and identity, women’s voices, and Christian teachings. Her latest work, Island of the Innocent, is no different, and unlike much of her earlier work, weaves together and traverses all those themes in one work.

Subtitled “A consideration of the Book of Job,” the work strikes more aptly as a meditation or a collection of meditations. In the life of the mind, an idea enters as a guest and refuses to leave. Writers, gracious hosts to ideas that they are, welcome the pushy idea warmly. Often, the idea’s friends tag along, and it becomes a party in the guesthouse of the mind. The idea, its friends, and the more permanent residents of the mind dance and twirl until they congeal into something else altogether, something too big for the mind to hold all at once, something that must get out, so it can be examined properly. The only way to resolve this tension is for the writer to write. This process is likely applicable to thinkers in every art form, but Ms. Glancy is a writer. In Island of the Innocent, she throws a dinner party for her house guests, their friends, and the more permanent residents and records their conversations on the themes raised in the Book of Job. The result is our treat.

In late October, I spoke to Ms. Glancy via telephone call about the quilting that occurred in this work, the poetics involved in re-telling stories from the Bible, and breaking all the rules of writing to tell a meaningful story.

This interview is edited for continuity and clarity.

***

Jaminnia R. States: What inspired you to write The Island of the Innocent and how did you enter this project? There are so many threads weaving together to create this consideration or mediation on the book of Job, and I am wondering what came first for you as the writer?

Diane Glancy: Well, first of all, I’ve always loved the Book of Job. I’ve always been a loner and sat around thinking about things, or meditating about things. And I like the way the mind works. Many different ideas pass through the mind when you think about one thing.

I took a while to write this book. Sometimes, a book comes quickly, and other times, they take their time. I did other things during the writing of this book. I would go different places and different events would happen, and I’d think, ‘Could I put that in the Book of Job? They don’t really fit.’

Native American history, my own driving through a blizzard, and my own puzzlement about different things. And the bible, as a whole, is also a great influence. Its many voices, many places, many writing styles. There’s a little contradiction or two in it. It’s just put together so crazy quilt-like, with a lot of different pieces. I had a grandmother who quilted. I always liked the way she would cut up our clothes and place the pieces together in different patterns. So I think that also was a possibility. I do the same thing [in Island of the Innocent]; this is a quilt work. I just wanted to try something new. I’ve written for a long time. I wanted to see if I could take all these incongruities and make a quilt, make a piece, make a book out of them.

I also like to give voice to those who did not have a chance to speak and Job’s wife gets shortcut in the Bible, I think. She didn’t get to say very much and those ten children who were killed, she had given birth to them. So she had a stake in this story, and she saw his suffering. So many of the pieces are in her voice—several poems and the longer Jehorah piece. I wanted a woman to be acknowledged.

JS: I thought that was so well done. The many perspectives. If I were to take out and read only the poems, it’s almost like a play. Everyone has a monologue, some of the animals even; everyone gets a voice. And that was enchanting to me as the reader, to be able to picture it alive as if the characters were talking to me in a spotlight from the stage. It took me a while to connect your discussion on poetics to what you were doing with the perspectives. But I loved this discussion on poetics and how the story of Job was being told over and over again, and the poetics applied to the perspectives as much as it applied to the words themselves. What works inspired that application of poetics to the narrative as opposed to the word choice? Are there any works you read that are like that.

DG: There are many experimental genre-crossing books, but there are not many Christian books like it. As far as poetry, there’s a sonnet in the book. There’s a sestina, a villanelle. That’s the more abstract poetry that doesn’t make sense at all, that kind of follows how the mind works—kind of an eclectic accumulation of images and thoughts and voices. So poetry as a genre itself breaks apart, then the book breaks apart into monologue, drama, and essays where I’m thinking about suffering and what it all means. These are things I think don’t go together. But we live in such a fragmented world, which gave me permission to write the way I did. The way that life just comes at you at different speeds, at different times, and in different ways. Sometimes you just want to say, ‘Give me a break.’ But I just kind of followed a natural experience of living: travel and working and writing and answering emails and thinking about things.

JS: When you were putting it together to send to an editor, what helped you put the pieces in order? How did you decide what goes where?

DG: A lot of it was chronological. What I wrote first, then what I wrote second, and then what I wrote to kind of continue the plot. There was some element of the novel: Job suffers, why does he suffer, he realizes he has some pride and some hidden attitudes, for which he repents, and then everything was restored, which was also a problem, because what were they going to do with their pasture now full of 14,000 camels? Even the restoration was a problem for Job’s wife. There’s a logic, in a way, from beginning to middle to end, but there’s also a wonderful illogic. And that tension between a story working and a story working against itself kind of intrigued me.

Then I would stop my writing and I would drive to Nebraska and look at all those artifacts on loan from the Smithsonian. I was driving along listening to the Book of Job on tape because I like to hear it in my ear, and I thought, ‘I wonder if this trip could go in the book?’ And yes it could, because I said it could. A lot of it was just claiming territory and putting a stake in the ground. This is where I stand, and I am going to do this.

I travel to Pittsburgh every winter in January, and I drove through a blizzard, that’s toward the end of the book. I was looking through my mixed heritage and came up with “Jump Suit” and that’s in the book too. It was fun to see how far away I could get and yet be within the context of the book. I felt it very exciting to take these risks. I’ve written a long time, this isn’t my first book. So you suffer the rules, and then after a while, you just take off on your own in the spirit of freedom. I thought, “Can I get away with it?” and apparently I could. It’s had pretty good reviews so far. [laughing]

Well, people ask ‘what exactly is this?’ or ‘what did you think you were doing?’ but mainly it’s been ‘Well, that’s not bad at all.’ So I want to do it again.

JS: We hope you do. Tell me about how and why the abstracts ended up at the beginning of each section.

DG: Well, I’ve been in academia for years, and you always put an abstract at the beginning of a paper that you’re going to send out for publication. I just thought, ‘I’m going to steal that idea for a creative book’ and put in an abstract. It’s because of academia. I wanted to borrow a little bit from every place.

JS: I see, so it was part of the quilt making.

DG: Yes, I’d say so.

JS: There are places, especially in the essays, where the quotes from the Bible either form or finish the sentences. I was wondering if those quotes came as a matter of your own meditating and connecting different passages to the Book of Job? Or did you use Bible concordances as a part of your research?

DG: Well, I think it was a little bit of both. I can go to one example, of where I had to insert a quote from Job into the piece so that it would fit in the book. It happened right in the beginning. [In “Versions of the Many-Versions-Of-Greasy-Grass”] I had been out to that area and I had written about it and I had this long piece and wondered ‘Where could I put it? Well, I’ll just put it in this book, the way my grandmother would take a piece of red fabric and put it next to something yellow.’

I have it here in my lap. <reads> ‘There is more than one story of the Battle of Little Bighorn. There are the stories of the birds. The gophers and the moles. There are stories of two women pushing their sewing awls into the ears of Custer when he was dead.’ There’s my grandmother and the sewing part, and the next line is right out of Job. Because I thought, ‘I’ve gotta make this fit’ so I just added it after the prose poem was written. <reads> ‘Thou liftest me up to the wind; thou causest me to ride upon it, and dissolvest my substance—Job 30:22.’ Well, that’s exactly what happened to Job or to Custer. His existence was dissolved, for inserting himself someplace he didn’t belong, which was in the Indian encampment. A lot of the time, I’d be reading Job and I would just love one of the passages and I would just stick it in the book and have to write a poem about it.

On page 52 there was a passage I liked, Job 36:32 <reads from “Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar”> ‘With clouds he covers the light…’ I just love that. I mean to think of God putting a cloud in the sky to cover the light. <continues reading>‘ and commands it not to shine, by the cloud that comes between.’

So all of these clouds getting in front of each other and pushing each other out of the way in the sky. It was a delight. And so I wrote the poem about the three friends Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar. Their monologues were much like these clouds that were in the sky. So that’s an example of how I found something in Job that I liked and I had to write something about it.

JS: What about “An Act of Invasion” on page 125? That one weaves in so many other books of the Bible.

DG: Oh, this is a talk I gave at Biola. It was a lecture on suffering. Can you believe that? It’s a Christian college. There weren’t a lot of people in the audience. I mean who would want to come to that? [laughs] This is a talk I gave on why Job suffered and on suffering in the Bible. I’m on page 126 now. 2 Timothy, John 16, I mean the Bible is full of suffering. 2 Corinthians, Philippians. It just doesn’t stop.

Suffering, which the Book of Job is about, builds character. There are a lot of good things about suffering and it seems to come pretty naturally anyway. You don’t have to ask for it to happen. Just sit there a while and here it comes. So what purpose does it have? I just wanted to explore that and how everybody in the Bible seems to suffer. The apostle Paul seems to go on forever about shipwrecks, imprisonments, beatings, and being run out of town, etc. So that was the topic of the talk, Poetry and Suffering, which is on YouTube, or it used to be.

JS: You’ve talked about this a little bit. I’m wondering if you can say more about how you connected the Native American history and your own family history to this text as well.

DG: Well, it’s always been part of my life. I’ve gone to church all my life, and that’s why I like the Book of Job. And I was a professor for 20 years and I taught Native American Literature. So that’s certainly a part of my life. When you do that for 20 years and you’ve heard the story of Job for 50 years…

It was just a natural part of my life. Native American literature, I’ve written many books about Native History, the Cherokee Trail of Tears, and Sacajawea traveling with thirty-three men on the Lewis and Clark expedition, and Kateri Tekakwitha, a 17th century Mohawk converted by the Jesuits. I just finished another book, Ada Blackjack, she was an Iñupiat, who went with four explorers who went to Wrangel Island 1921-23 and was the only survivor. I always love to give voice—I’ve always done this, given voice to those who did not have a chance to speak. That’s kind of my forte. You know when you write a long time, you return to some of the same techniques, and I spent more time on what I liked.

So the Native American and Job’s wife certainly got a voice in the book. My thoughts just keep returning to certain things.

JS: Thank you for that honesty. I think that’s important for students of literature to know, and I also think it’s also important for students of history to have permission to imagine, and I think what your work has done is demonstrate what happens when you take the liberty to do both. That was my biggest takeaway as a writer. More than anything else, I just really appreciate your example of that.

Especially wanting to write non-fiction, and wanting to write it for children, and to speak for those who haven’t been spoken for honestly, it requires us to break the rules of history, which is ‘you can’t imagine, you can’t make stuff up.’ ‘Yes, I can, because you did, and I have this heritage in me and it’s fair for me to imagine based on what we all know, and what the truth could have been. And we get closer to it for having done so.’ So I really appreciated that.

DG: Well, you also have to know every once in a while you get in trouble. I remember after the book on Sacajawea came out. I gave her a lot of dialogue [in the book]. I was at a history conference reading from it. The first hands to go up after, of course, were the historians, the real historians. They said, ‘Well, you can’t give voice to somebody that you weren’t there to hear, and take down her dialogue.’ I said, ‘Well, yes you can.’ To get somewhere in the neighborhood of what it could have been, to fill in the missing parts of history. You just need to know you’re going to get people who are going to tell you that you can’t do that. They’re sticklers about the exactness. But go ahead and do just what you want to do.

JS: One of my professors, I was watching him recently. He was saying history is complicated because it’s not about events, it’s about human relationships. Just that shift changes everything. Human relationships are complex and motivations change and conflict with one another, even in one person. We have to start telling fuller stories. We have to do that.

Thank you so much for taking this time, and for putting this book out in the world. It has really impacted me as a writer, as a student of history, and also, as a Seeker of truth.

DG: Well, you are quite welcome.