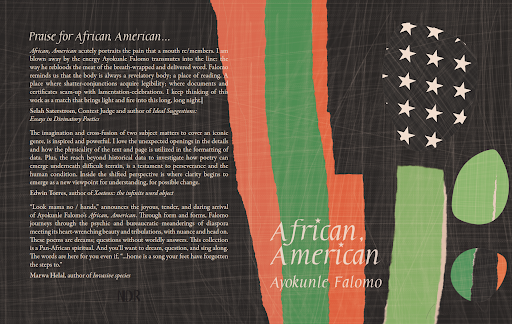

Our Interviews Editor Esteban Rodríguez talks with poet Ayokunle Falomo about the importance of family, writing from the perspective of two nations, and his newest chapbook, African, American (New Delta Review 2019).

Esteban Rodríguez: What were the influences and inspirations behind African, American?

Ayokunle Falomo: I suppose I’ll start by saying that in 2017, I’d just finished a project that largely had to do with the intersection of personal fears and family history when I decided my next project was going to tackle national history: I wanted to explore what being Nigerian means to me. I started writing poems then and that remains an ongoing project. Later, I began to explore more and more what being (a naturalized) American means to me. The chapbook came out of that dual exploration.

In so many ways, the chapbook actually is not shy about pointing out its many inspirations: my immigration/naturalization documents; the immigration process itself—lengthy, draining and depressing; an ignorant comment by a friend; the fraught concept of nationhood; being Black in America; the 2016 election; reading, listening to and learning from folks I look up to—like Ariana Brown, Loyce Gayo, Mwende Kwatiwa, Solmaz Sharif, Layli Long Soldier, Marwa Helal, etc.—who are invested in the work of interrogating (if not dismantling) the structures of empire and colonialism; history, and so on and so on.

ER: In many points throughout the book, the speaker contemplates the realities of living in the U.S., especially when it relates to his younger brother, whose behavior could carry consequences that negatively affect his life, given the way in which American society puts black bodies at constant risk. I’m thinking of the poem “My Brother, Tamir” and the following lines:

There is such a promise as school to prison

Pipe line. Sounds almost made up. Kinda

Like the Loch Ness, this beast that’s all

Stomach. Don’t even ask… It makes

A memory of the bodies of brown and black

Boys especially. Yes, I’ve even made him

Write summaries of what

He understands about being

Swallowed whole by a rip, because

It is never too early to let a black boy

Know the future America has mapped

Out for him. Dead or alive, a sentence

Is a sentence.

How has the American landscape (societal, political, and even geographically) shaped your approach to a poem and how you write about familial subjects?

AF: I suppose in a way the family is one’s first country, really. In which case, it has its own landscape too. Sometimes, both landscapes mirror each other in ways that are uncanny and I think that’s how I’m able to approach and broach the subjects (of family & country) as well as the subjects that show up in my poems. Ultimately, I am interested in interpersonal relationships, how we relate to one another, which is what I think politics, at its best, is concerned about.

On a more personal note, while there were many more ruptures before that, coming to America was the first undeniable evidence of rupture in my conception of what family is: largely shaped by shared space. The absence of that spatial proximity to my mother and siblings for seven/eight years mirrored, I suppose, the distance I felt towards America/American identity. In a sense, I was trying to understand America through that initial rupture as well as understand that rupture through America, if that makes sense.

All I’m really saying is that I believe both to be the same landscape, albeit an emotional one. As was the case for many of the poems in the chapbook, nostalgia, for example, is a powerful (and useful) feeling to jumpstart a poem whether the object/subject is Nigeria or my mother.

ER: Poetry often blurs the boundary between what is personal and what is fiction. How much of your real life makes it on the page? How much made it in this book?

AF: More and more, I have been attempting to write poems that stray from the autobiographical–it feels impossible–but the simple/direct answer to the question is that most, if not all, my poems are drawn from my personal life as well as through research. Especially the ones from this manuscript. With the exception of tiny details that might have been changed for the sake of “being true” to the poem or for whatever reason, there’s little fiction, if any. Fiction being, in this case, as I understand it, something made up. I mean that if I say something happened in the poem, then it did. Memory of course complicates that. It might not happen exactly as I say it happened, or when I say it did. Also, depending on who the speaker is, what is considered ‘real life’ differs. Which is what I’m almost always most interested in. That’s usually where the poem starts for me. The moment in our (inter)personal lives when the lines between reality and fiction are blurred. The moments I find myself wondering is this/are you for real? It’s not fun in real life, but definitely fun for poems.

ER: How do you hope African, American interacts not only with readers, but with the entirety of your work?

AF: Since I think African, American is interested in both fracture and intersection, my hope would be that readers will find the ways in which our collective stories intersect, fractured as they might be. I’m hoping that what resonates more than anything is how certain decisions (political or otherwise) have impacts on the nuclear, personal level. It’s far too easy to fall into the trap of having conversations about issues such as (im)migration, citizenship, nationality, patriotism, school-to-prison pipeline, state-sanctioned violence, etc. in a theoretical way that ends up diminishing (or even erasing) the reality that the lives of real people are at stake, even as they become national/global talking points.

As the chapbook is, I want to believe, in conversation with the rest of my work, even as I am trying now to veer from strict autobiography, I want to hope that it continues to teach me how to look for/at how the personal speaks to the larger contexts of our historical, national, and global lives.

ER: What work is speaking to you now?

AF: At this specific moment, Fleet Foxes’ Sun Giant. In the past month, Baldwin’s essays have been and I have attempted speaking back. At any given moment though, lines from poems and song lyrics are always running through my mind. Over the course of the summer, in addition to individual poems, I read Terrance Hayes’ American Sonnets…, Li-Young Lee’s The City in Which I Love You & The Undressing, Romeo Oriogun’s Sacrament of Bodies, Gwendolyn Brooks’ Annie Allen, The Essential Gwendolyn Brooks (ed. Elizabeth Alexander), Carl Phillips’ Quiver of Arrows, Nancy Reddy’s Acadiana, Robert Bly’s Leaping Poetry, John Ashbery’s Selected Poems. Most of these I’d read before, some several times, and all of them spoke and are still speaking to me. Also, since I’m teaching an introductory creative writing course this semester, I’ve been primarily reading/rereading poems and stories I’m excited to bring to class, including/especially those by, but not limited to, Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, Randall Kenan (who sadly just passed), N. K. Jemisin, Ebony Stewart, Ariana Brown, Aris Kian, Joshua Nguyen, Lupe Mendez, Jasminne Mendez, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Patricia Smith, Kaveh Akbar, Paige Lewis, Ross Gay, Marwa Helal, Jennifer Chang, Eduardo Corral, and, and, and…

ER: What are you currently working on?

AF: As to what I’m working on at the moment, aside from a manuscript-in-progress and the occasional poems that come to me here and there, I am working on (and deeply committed to) seeing and listening to the world in a way I hadn’t before, being kind to myself, and with a new semester just starting, being present and offering the best of myself: as a student and as a teacher.

ER: What’s one piece of writing advice you could give your younger self?

AF: I struggled to choose which version of my younger self I should direct this advice to. Me at age six, or me at 6:00 am this morning? In either case though, I’ll say breathe. Or, to put it another way, allow room for breath.