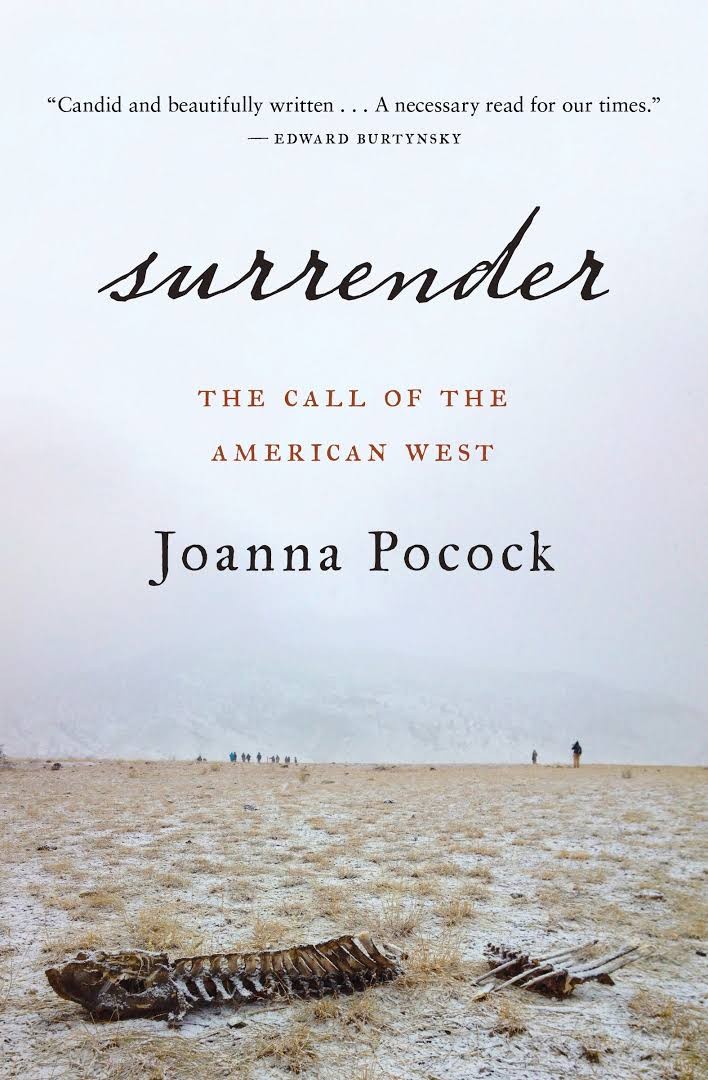

Joanna Pocock’s eco-memoir Surrender opens with rhythm, specifically the rhythm of the human lifecycle: mundane repetitions leading to ennui, and the dreaded advent of a mid-life crisis. Feeling caged by the familiarity of London, Pocock, her husband, and their seven-year-old daughter decide to make a drastic change. “The mid-life crisis package I was handed came in a box marked with one simple word,” explains Pocock, “Montana.”

From the outset, Surrender sets a pattern that the rest of the book will follow. Within the first chapter, we learn of Pocock’s loss of her 52-year-old sister to cancer, her own mid-life crisis, the history of copper mining pollution in Butte, Montana, and the retreat of glaciers in Glacier National Park. We encounter quotes from Donald Trump and Shawnee Chief Tecumseh, Thoreau and the infamous Bundys. In less confident hands, her wide-ranging subject matter could have created a book that felt disordered. Yet, Pocock melds these worlds with brilliant ease.

Unfolding in linked essays, Surrender follows a narrative structure anchored by Pocock’s personal life. Her struggle with losing her parents in Ottawa and the onset of menopause become touchstones for the book, while also serving as human-scale versions of the natural cycles she examines—in rivers, forests, high deserts. The geography of the book echoes this cyclical pattern too, beginning in London, heading to Montana (and other parts of the greater American West), then ending up in London again. (In this, one is reminded of “the Hoop,” the path walked by the Nez Perce each year before European settlers invaded their lands, which figures prominently in Surrender as well.) Pocock’s writing style is spare, allowing the landscape to speak for itself through lovely photographs interspersed through the text. She builds an urgent call-to-action through concrete details. For me Pocock recalls the likes of Joan Didion, Annie Dillard, and Rebecca Solnit, and their own transcendentalist forebears like Emerson and Thoreau. Pocock is wonderfully well-read in naturalist traditions, and my list above comprises just a few of the stars in the constellations of influences that Pocock herself invokes. (Reading the included bibliography at the back of the book is a worthwhile pursuit in itself.)

While covering personal and ecological crises, Surrender builds around a theme of looking. After her mother dies, Pocock states, “I am a fan of open coffins because I think it’s important to look at death. To get close to it.” Throughout her memoir Pocock pursues new experiences, taking readers along to unsettling wolf trapping certification classes, heart-racing bison hunts, and “eco sexual” conferences. Along the way she encounters eclectic characters, from the nomadic “rewilder” Finisia Medrano to far-right militia groups like the Three-Percenters.

As a lifelong Central Oregonian, reading the history of what I consider my region (roughly Central Oregon, Eastern Oregon, Idaho, and Western Montana) was by turns enlightening and nostalgic. In the descriptions of Bison Bridge—a group dedicated to keeping old practices using every part of the bison alive—I recognized the types of people I grew up with in rural Central Oregon: trappers and Boy Scouts; homeschooled right-wingers and homeschooled hippies; 4H and ranch kids. In the “audience members laughing” during a demonstration of what a trap can do to “‘non target’ animals—like your dog” at a showing of the anti-trapping documentary She Wolf, I saw the face of a boy who grew up down the street from me—a boy who not only caught a family’s dog in his trap, but proceeded to laugh gleefully at the fact that the dog lost its leg as he told me the story.

What I admired most about Pocock was her willingness to engage the complexity of other people, herself, and history—from truly touching moments with Finisia, to Pocock’s hilarious struggles with basket weaving (“It was the wonky handiwork of a neurotic, domesticated city-dweller”), to the chilling violence of Kit Carson. My familiarity with Pocock’s setting had me nodding as she identified bizarre overlaps between Left and Right in the West—both playing on another idea of “cycles” in the book. “Both groups,” she says, “seemed to believe that in order to have a future, we must craft it along the lines of an idealized past.” The main difference, as Pocock discovers, often lies in which past is idealized: Western frontier days when the government had little control over law and order, or the Paleolithic era when people lived off the resources of the lands. “Both schools of thought share a mistrust of the system,” but where one sees the earth as a resource to exploit, the other sees it as something to preserve, conserve, even love. The tension she captures is very true to my own experience.

Though published in 2019, Pocock’s observations hold added weight in the wake 2020, and against the backdrop of the West’s catastrophic forest fire season. The overlap between Left and Right was already tenuous; there seems to be less common ground today. Because of this, her constant investigations of ecological disasters—from the heart-rending story of the Blackfoot River, to newer threats like the Donlin mine in Alaska—left me with profound anxiety.

About halfway through Surrender, Finisia—then a new acquaintance—leaves this inscription in Pocock’s copy of her memoir Growing Up in Occupied America: “With understanding comes brevity; with wisdom comes sorrow. Sure ya wanna step? Sounds like a slippery slope to me.” The warning is for Pocock, but it is also for us: with wisdom comes sorrow. The land in the West “does things to you that cannot be undone,” says Pocock near the end of Surrender. Likewise, Surrender, does things—imparts knowledge, inspires urgency—to a reader that cannot be undone. Pocock conveys the sense of dread we should feel bluntly. It can feel like drowning. Yet, honoring the cyclical nature of the book, we move from hope to dread to hope. Pocock throw us a rope: her own story, the battle of small actions, of embracing wildness wherever she can, of looking at the bad situation squarely.

Early in her book, Pocock characterizes a “Montanan conundrum” as “beautiful, desirable, complicated and rife with historic problems.” It’s a network of problems that cannot be summed up or solved easily, that once noticed cannot be ignored. It is the liminal era we all inhabit now. Through the diverse cast of characters and approaches she poses the question: Can we unsettle the West? It seems unlikely, unless we the inhabitants of the West are unsettled first. Though it will bring you enjoyment through craft, keen observations, and its cyclical structure, I can guarantee that reading Surrender will not bring you peace of mind. And that is exactly as it should be.

Editor’s note: to read an excerpt from Joanna Pocock’s Surrender where Pocock describes meeting the person and work of Finisia Medrano, who “[lived] on horseback for 35 years replanting the wild gardens of the West,” visit here, as well as Pocock’s essay “Death of a Radical Rewilder” at LitHub. Visit here to watch a trailer for a film documentary on Finisia’ life.