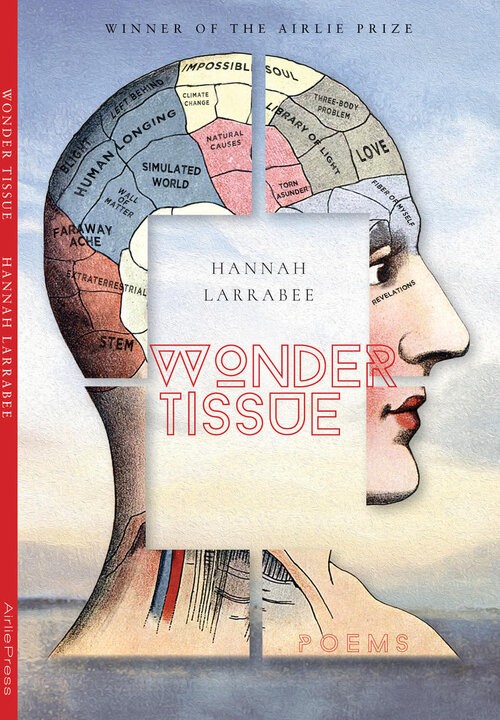

Wonder Tissue is Hannah Larrabee’s debut poetry collection, and the winner of the Airlie Prize. The book is organized into two hemispheres of the brain—right, then left. Even so, it pushes gently but with determination against this binary. One of the epigraphs to Wonder Tissue is poet Jim Harrison’s quote, “We pretend that the brain is binary, like a computer. But it’s not. / It’s completely holographic.” A hologram exists by way of light’s illumination in three dimensions as opposed to the limitations of a two-dimensional page, a binary of black ink on white paper, of top-down and left to right margin. The word hologram comes from the Greek holos, meaning “whole,” and gramma, meaning that which is drawn or written. The physical brain is one whole contained in three dimensions, but in what way can it be drawn or written?

Wonder Tissue endeavors to capture a multidimensional glimpse of one speaker’s way of thinking and being in the world. The book proceeds by way of illumination, with the idea of wonder tissue itself containing more than just the human brain, but the wonder of there being any such tissue at all in the vast mystery of our universe.

The collection spans the range from love poems and poems of the body to depictions of a body in space, a body in orbit around another body. To the speaker in these poems, the way science endeavors to make sense of the wonders of our bodies is truly spiritual, and belonging to a spiritual universe necessitates a whole and embodied belonging, being “earthly,” as at the end of the poem “Mandolin Busker”:

The world

rots away like apples in the fall. Buskers and

Salvation Army bells, everyone is wanting,

everyone is earthly. But I can feel every fiber

of myself being pulled up toward sky, and behind

sky, darkness, and behind darkness I am reassembled,

I am the deer standing head-bowed at the fruit,

light years away from what was once a painful

human longing, a hunger I carried like a backpack

into the woods and never returned.

“Everyone is wanting, / everyone is earthly,” the speaker asserts, even the mandolin busker and the Salvation Army volunteers—each hoping for others’ small generosities like apples before the rot rushes in. And such generosity we each are made of, our bodies “reassembled” from centuries past, and to such reassembly they will continue returning.

Part of the pleasure of reading Wonder Tissue is how expansive Larrabee makes each moment of observation, each image, always with an insistence on the spiritual reality of the body. One of my favorite poems in the collection is “Basalt,” part of which reads:

I want to tell you that in Nova Scotia my father

let me loose on a beach with cliffs exposing tree

fossils, leaf fossils, I was a child—it was a wall

of matter so important I could feel the bitter

sting of human hands. We have been framed

incorrectly in sin. Touching the surface of that wall

was Eden. Wanting to take from it was Eden.

I sit close to you and it comes so near to me:

a meteorite, the thing we cannot predict. We have

been framed incorrectly by time. I have accepted

your words before, felt the strike-slip of your body.

There is so much beauty at work here. Fossils open up the speaker’s mind as a child into a grander sense of time, and thus a grander sense of belonging. The way “I was a child” belongs here in the list of fossils coaxes shivers up my spine. Of course what follows then are challenges to the root of Judeo-Christian conceptions of self—that “we have been framed / incorrectly in sin,” that “touching” and “wanting to take” are the truths underlying the gifts of creation.

Amid our ongoing crisis of mortality, the catastrophe of climate change, the crisis of a final loneliness and entropy, Wonder Tissue offers Eden, offers mercy. If we can muster the courage to touch its surface, to want “to take from it,” paradise is right here, in the beloved. And when the taking is holy, when admitting to the want is admitting to the sacred, that is love.

Between the hemispheres of the text, Larrabee offers a bridge in the form of the one poem, “Corpus Callosum.” Latin for “tough body,” the title is the neuroscientists’ name for a middle part of the brain that itself functions as a bridge of the hemispheres. But the text of the poem offers the image of a very different bridge: “the land bridges / we’ve designed, those / elaborate highway / overpasses // so animals / can continue / their migrations.” The final stanza of this short poem launches from this wildland-urban interface to the nature of belief, to humans’ “guilty / ingenuity.”

In the first poem of Wonder Tissue’s left hemisphere, “Wings without Bodies,” the speaker describes a friend’s story about a canoe trip. At one point, the friend looks up from the canoe and sees “flock of birds that were not birds / but wings, wings without bodies, moving in perfect fluidity, wings / revolving around some center point.” The friend wants to alert their partner in the canoe, but is unable to find the words to do so. That leaves just the friend to witness, “so it was / just you and those wings without bodies; it was perfect and lonely and / terrifying; all things God wants us to feel and promises.” If the speaker’s God wants us humans to feel this perfection and loneliness and terror, all holy, then those feelings must be ones with which God was first familiar. And what are we to make of a God who knows—and perhaps even invented—loneliness?

Larrabee isn’t the first poet to wonder at this question. I immediately thought of Rainer Maria Rilke’s conception of God’s pitiable loneliness, as I admittedly do often: “What will you do, God, when I die? / …You lose your purport, losing me.”¹ In an earlier poem in Wonder Tissue, “Convent of San Marco, Florence,” Larrabee’s speaker envisions God similarly: “…God grows old / and marks with silence / the notation of his loneliness / emerges like slugs in the rain / with no apparent agenda / but to move on and through / feeling, that is what it is / the body you reveal / to me, the exactness / of lungs beneath breasts.” Larrabee always moves fluidly from the natural world to the spiritual one, and to the worlds of intimacy between lovers.

Wonder Tissue insists that the boundaries between these spaces are porous, that their interconnection is one definition of holiness. What boundary can there be between my body and the body of the beloved, between my body and the body of earth, of sky? Toward the end of the poem “Looking for Love in a Simulated World,” Larrabee writes,

And through it all the singular desire

to be two places at once: 1) in the infinite

arms of trees, and 2) against a wall

where her hands have put me, all theories

in a state of proving themselves.

One desire from one body to be in two places in relation to other bodies constitutes a multidimensional whole. By seeing paradise among and between us, in our porousness and reassembly, Larrabee insists upon the spectral nature of our bodies, of sacred nature, like light.

I fear my review hasn’t even come close to capturing the broad range of wonder that this collection covers. Here’s but a sense: you might love Wonder Tissue if you need a text that celebrates how holiness looks a little different than what you were taught to worship (“you might / think it all through in careful / mathematics, but it is no one’s fault / if this is what you love”), if you’ve ever needed there to be more poems inspired by Sufjan Stevens, if you have been troubled by the many warning bells of climate change clamoring for redemption, if you are compelled to see living creatures as prophets, if you believe in spirt but also in aliens, if you have read and loved Rilke’s intuited depictions of a lonely God, if you have felt any number of earth-shattering insights hit you in the middle of gazing upon the layers in a cliffside or listening to the breathing of horses, if you have felt the frustration of not being enough in this world to carry all that this world asks you to carry, or if you want nothing more than to be struck with the surprise of sudden beauty like naked salvation.

In the poem “On Earth,” Larrabee writes, “When a trout is lifted from the water, the universe / is lonesome. I wonder, is it peaceful out there // in all that is unending?” The wonders that this collection provides are as unending, as spectral, and as whole.

¹ “What Will You Do?” by Rainer Maria Rilke, trans. B. Deutsch and A. Yarmolinsky. https://poets.org/poem/what-will-you-do