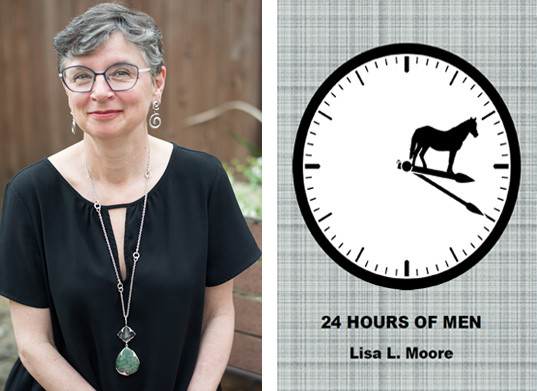

A review of 24 Hours of Men (Dancing Girl Press & Studio) by Lisa L. Moore

“Here’s my love for that loss,” Lisa L. Moore writes at the end of her poem “Raising White Men,” and given that the poems in her chapbook 24 Hours of Men depict the naming and branding of animals, I nominate this line as a brand for the book. Here are poems steeped in love, stitched with loss. “Why is the measure of love loss?” Jeanette Winterson asks at the beginning of her novel Written on the Body, and isn’t that what every poet, every person wants to know? In “Hymn” Moore advises:

Don’t long for the thing that doesn’t love you.

You can’t make it stay. Praise instead the blind

imperfect grasping, the way from sound to silence,

from me to measureless.

‘From me to measureless’ strikes me as a lovely reformulation of Rimbaud’s prescription: “A poet becomes visionary through a long, boundless, and systematized disorganization of all the senses.” Indeed, Moore writes poems of vision and of sense, of senses combined and difficult and vexing, as in “Poisoning Gophers, 1977,” where the speaker recalls a childhood chore of farm life, mixing strychnine with oats and dropping the mixture down gopher holes on a seventy-acre pasture. ‘The sweetness stayed with me,’ Moore writes of this pastoral scene, ‘but also//the heavy poison bucket. I want now/to lay down the strychnine-coated spoon.’

As the book’s title indicates, men are pervasive, a constant force in the life and memories of the poet, from the current occupant of the Oval Office whom Moore does not name in the opening poem, “Inauguration,” to violent, abusive family members, anonymous harassers, and ‘these sons of sister mothers,’ i.e., nephews and a son raised by lesbian parents. In the brilliant poem “Lesbian,” Moore reconfigures the word as she locates the Greek island Lesbos from which it originates in both history and current events, noting ‘Lesbian camps hold six hundred thousand migrants from the Middle East.’ With talismanic power she writes:

Names out of Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan: Yousef Mohammed, Ammar Saker, Amal and her six-year-old daughter, speakers of Persian and Arabic, poets and engineers and pharmacists. And now they are Lesbians.

These poems rename and reclaim time and race, gender and relationship. They move gracefully between public witness and intimate recollection. Moore navigates pains personal and political, writing about her son’s near-fatal car accident and police killings of citizens of color. She examines religion as both cause and cure of wounds in poems such as “Nephews” and “Maundy Thursday At the Megachurch,” which ends, after the speaker emphasizes her secular detachment, with the confession, ‘But the host burns in my hand.’ “Inauguration” establishes an orientation to feeling that is deeply rooted in place, from its opening line – ‘And so I turn the heart’s soil’ – to its last – ‘this broken ground my prayer,’ in a way that recalls the work of Seamus Heaney and Louise Gluck. But the boldness and originality of the title poem, which serves as the final one of the collection, is all Moore. ‘I was surprised to see their cunts,’ she begins, and goes on to observe that ‘Male genitals are just women’s, pulled/outside the body.’ The poem investigates toxic masculinity and the way it damages everything around it, especially relationships between women and men. It ends, mid-yoga-pose, on a note of hope:

...my heart melted for men’s vulnerability, which opened out between my friends’ legs like flower after flower after flower.