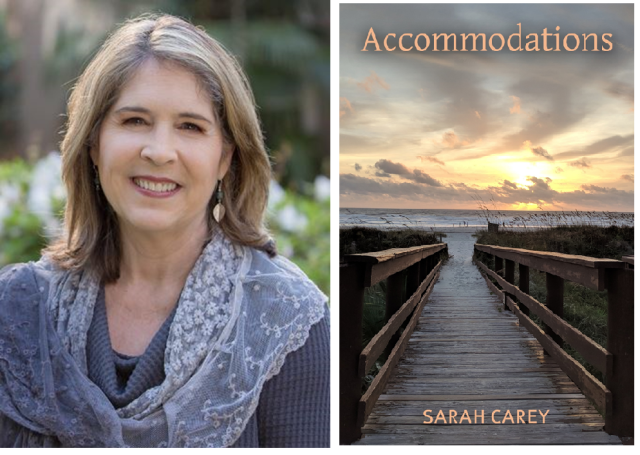

The poet Sarah Carey, author of the chapbook Accommodations, not only shares the same first name as mine: more significantly, we share the same generation, and the same weight of daughterhood as our parents make the last descent. One advantage of being older, of writing from a place of more life-experience, is the ability (if you are fortunate) to move more fluidly from one’s personal view to wider concerns and back again; a life-lens, if you will, with an ever-increasing range of focus, even as some aspects of life (parental death, other losses) decrease. Consider these lines from “Heel of a Loaf”:

Loaves are history,

Gone as our ancestors

Yet stuck to our ribs forever

As Sarah Carey demonstrates in these pages, there is something very inspiring about poems which gather us around memory’s table while also inviting us into the hurricane’s hungry maw. These poems move confidently between images of intimate family meals, a father’s decline, and a storm’s vast destruction, then back to center. These lines from “First Day of Hurricane Season” embody the deep anchor of the collection:

Ocean sediments will stay roiled

for weeks before they settle,

but I hit bottom,

and learned acceptance long ago.

Breathe the slow wind-

another storm is always coming. (“First Day of Hurricane Season”)

It is indeed hurricane season within these pages: as storms gather and try to swallow the Florida terrain, these poems also seek to weather the near-drowning grief of a father’s death. The poet navigates and negotiates the territory between what human beings have wrought on a climate level and what we experience in the small universe of personal grief, a tremendous and worthy task. It is a form of accommodation: learning to navigate between extremes–

As the fluids left my father’s body,

I watched him track my tears, a salt river,

Smelling of seaweed and grief.

His goodbye would see me through

just one more storm, the mopping up I’d do,

so sure we’d not be swamped again.

When I was as tiny as a country

seen from light years away, he held me

high above the swirling sea, that was

the beginning and the end of everything. (“Before Landfall”)

Later in the collection, the poems begin to make other accommodations to life passages: homes made and then unmade, lives replanted elsewhere, along with the more mundane demands of a certain stage of adult life (plumbers, neighbors, household marital arguments). This section of poems is a testament to the poetics found within a quiet life, a map showing how we might go beyond the kind of resignation and endurance which can creep up unawares in later life, into something more. Let’s face it, some experiences are prosaic beyond rescuing, even for the best poets; the danger of a too-well-cushioned life. These poems don’t try to gussy up the normative with a layer of unwarranted significance, as contractors tear up kitchens and coffee pots bubble: yet there is a poetic intelligence shimmering through these daily encounters that animate even a granite counter, a convection oven:

When I break in the oven

to convect, you’ll forget the grief you spent

not eating when your father died. All we paid

for what we craved, our second chance.

we’ll start again in softer light, in which we’ll see

each other, aging in the stainless.

Estate planning, ancestry, memory-drenched belongings, the genetics we do or do not pass on: these are the concerns of a poet who knows she must find a center in the present while also organizing what she will leave behind, and what she hopes to carry forward. The poems in Accommodations are mostly constructed of the kind of forms which either compel or contain this sense of motion; either the forward momentum of tercets, or, more often, the still center of surety engendered by a couplet’s more balanced pairing.

The last two poems of this collection, “What We Carry” and “At Rhine Falls,” transport us to another country, literally, as the scene changes and we are far from Florida’s sea-washed flora and fauna; instead we are walking around Paris, and the Rhine. The poet brings her own hard-earned perspective with her as the focus shifts again: we see America from the perspective of another country, the changes wrought by time both personal and global, and how tempting it is, in order to cope yet again with change, to live in the past:

We’ve survived shrinking human concern

for endangered species, carcinogens

in pesticides, too much ultraviolet,

refuse to say we live in a threatened habitat

existing instead in separate fantasies

of what our lives used to be

However, the temptation (though great at times, I know) to seek the comfort of earlier times, earlier illusions, when youth was the only country–a time before the inescapable awareness that the world is suffering in ways previously unimagined–does not ultimately carry this poet away. If there is any true reward for making it thus far in life, for pursuing an ever-awakening consciousness, it exists in moments of true grace, moving forward into hope, as in the closing lines of “At Rhine Falls,”

My pilgrim heart possessed, my face awash

with spray, I close my eyes, draw breath,

and press my step-grandson’s hand,

which holds his father’s firm,

as the pounding water scatters foam

below us, lacy as the veil he may raise.