You do not have to be good.

-Mary Oliver

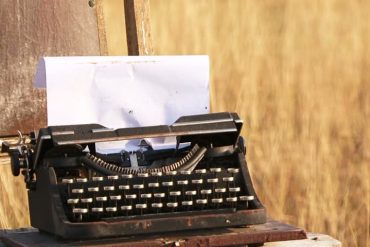

I am enveloped in a sea of golden husks. Stiff and strong, they prick my face as I lie down. The sun is shining and a few clouds dapple the sky. I close my eyes and hear the rush of the wind as it streaks through the amber waves of grain around me. This is my America: quiet to most but insanely alive. My bare legs are the first to rest, then my bottom, lower and upper back, and finally my head, upon the coarse soil. Some clumps of dirt give way to my weight and become dust. I think of how unique this is; how I am the only one doing this in the field behind my house. I never see anyone else run and disappear in an ocean of wheat. From afar this looks huge: acres of wheat bursting through the soil, reaching towards the sky, vast and intimidating. While lying down I feel like a jungle cat, unseen and easily able to surprise anyone or thing that comes my way. But I’m the one that is surprised. In the earth that crumbles there are worms, above me insects are hovering and hawks are looking for any field mouse who dares to mistakenly leave the safety of his burrow. I tend to think this field is chaos. It is, isn’t it? I mean, from afar the reason I love running through it is because its hugeness invites me to; just like a lake, it begs to be disturbed. But from down here it’s ordered. And this field is ordered: rows upon rows sewn into the broken earth, hoped by the farmer that his measly seeds will break through the earth yet again and bring in a bountiful harvest. I’m thankful for something as ordinary as this field: it takes me out of the busyness of my parents’ and others’ lives and brings me into the business of the bees and worms and grain constantly growing and changing and depending upon each other in the way that I long to depend on others–in a necessary way to let life keep on going.

Growing up on the prairie I loved nothing more than being outside. I could run, play make believe, and I could easily let my mind wander. Besides the wheat field behind my childhood home, there was a creek where I would fish. If I was lucky, I would catch a ride to the only lake in the state that would not freeze, Nelson Lake.

Buttressed by a power plant to the south and a coal mine off in the distance, Nelson Lake stayed warm–and still does–during the winter, like a type of natural hot spring found in Iceland, only Nelson Lake’s warmth is unnatural.

From an early age I found it odd that just outside of my small town there was a lake that would not freeze. Instead of pretending to be Jesus (like my naive childhood theology would have me believe) and walk on frozen water, I would slowly draw myself up as I entered what I thought was the refreshing, warm water of Nelson Lake. I did not know, then, what I know now about unnatural things.

More than ten years after my childhood and adolescence has ended, North Dakota is experiencing an oil boom. Good for moneymaking, and good for corporate pocketbooks, the land of North Dakota has come into national focus. People who are jobless in other parts of the country come flooding in to North Dakota looking for work, financial safety, and a place that is rumored to be quiet.

These floods of people, though, help us see what North Dakota is up against: maintaining its ties to the land and its ability to dictate how it is used.

Theodore Roosevelt, governor of New York, 26th president of the United States, and a short-term resident of North Dakota, shaped and forever changed by the Badlands, told the residents of Arizona how to handle the Grand Canyon in his speech on May 6, 1903, and it seems just as applicable to North Dakota today: “Leave it as it is,” he said. “You can not improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it. What you can do is to keep it for your children, your children’s children, and for all who come after you, as one of the great sights which every American if he can travel at all should see.”

It is not insignificant that the man who became known as the great conservationist spent his formative years in North Dakota. Roosevelt continues in his “Speech at Grand Canyon, Arizona,” that “[w]e have gotten past the stage…when we are to be pardoned if we treat any part of our country as something to be skinned for two or three years for the use of the present generation whether it is the forest, the water, the scenery.”

What Roosevelt knew, and what we all are striving to see, is that we are creatures on a finite planet. The Bakken oilfields, drilled and harvested, will run dry and the boom will be over. The money that is coming into the state now cannot be duplicated elsewhere; North Dakota’s model for staying in the black is not applicable to every state in the Union.

Wendell Berry, the essayist, poet, farmer, agrarian, and the father of the local farmer’s market, encourages us to think about the local economy. Economics, as Berry points out, is about how to best make money, it is separate from the economy. (The word economy can be traced back to the Greek word oikonomos, “one who manages a household,” derived from oikos, “house,” and nemein, “to manage.” From oikonomos was derived oikonomi, which had not only the sense “management of a household or family” but also senses such as “thrift,” “direction,” “administration,” “arrangement,” and “public revenue of a state.”) The economics of North Dakota might be good with more money being poured into the state, more money for investing, but the care and good use of the land are at stake.

North Dakota is in a peculiar place at this time in history–financially sound, with low unemployment and coveted wide-open spaces, North Dakota appears idyllic to a nation recovering from bad economics. But the hard reality of the mighty oil boom in North Dakota is that a series of questions is on the way: How do we clean up water polluted by oil? What will we do if the oil that is fracked leaks into Lake Sakakawea or the Missouri River Channel? What will we do when the wells run dry?

But where there is large industry there is also the opportunity to be prudent. The state legislature has already allowed drilling to take place in the Little Missouri State Park. Land owners, understandably, are lured by the idea of large profits and less work on land that is difficult to farm and ranch. But at what cost is the “success” of North Dakota putting the long-term vitality of the state under?

The environmentalist and political scientist David W. Orr believes we need to redefine success: “The plain fact is that the planet does not need more successful people. But is does desperately need more peacemakers, healers, restorers, storytellers, and lovers of every kind. It needs people who live well in their places. It needs people of moral courage willing to join the fight to make the world more habitable and humane. And these qualities have little to do with success as our culture has defined it.”

Perhaps the questions North Dakotans can now start asking are ones encouraged by Wendell Berry in his book Home Economics: “What is here? What will nature permit us to do here? What will nature help us to do here?”

For generations North Dakotans have lived off the land. The Red River Valley proved to be some of the best crop land–literally–on the planet; the prairie west of Mandan is good for cattle and livestock; the muddy Missouri, before it was dammed, flooded to help plant new cottonwoods and allowed for successful hunting.

The prairie of my childhood hid coal and oil that is now being extracted, slowly warming and weirding the planet. And North Dakota stands at a crucial time with the ability to legislate and say No, rather than prostituting herself out to Big Business. When asked about his successes by students, the Trappist monk – Thomas Merton – gave this advice: “Be anything you like, be madmen, drunks, and bastards of every shape and form, but at all costs avoid one thing: success.” Maybe North Dakota should do the same.