“It will only be love

that I love you with.”

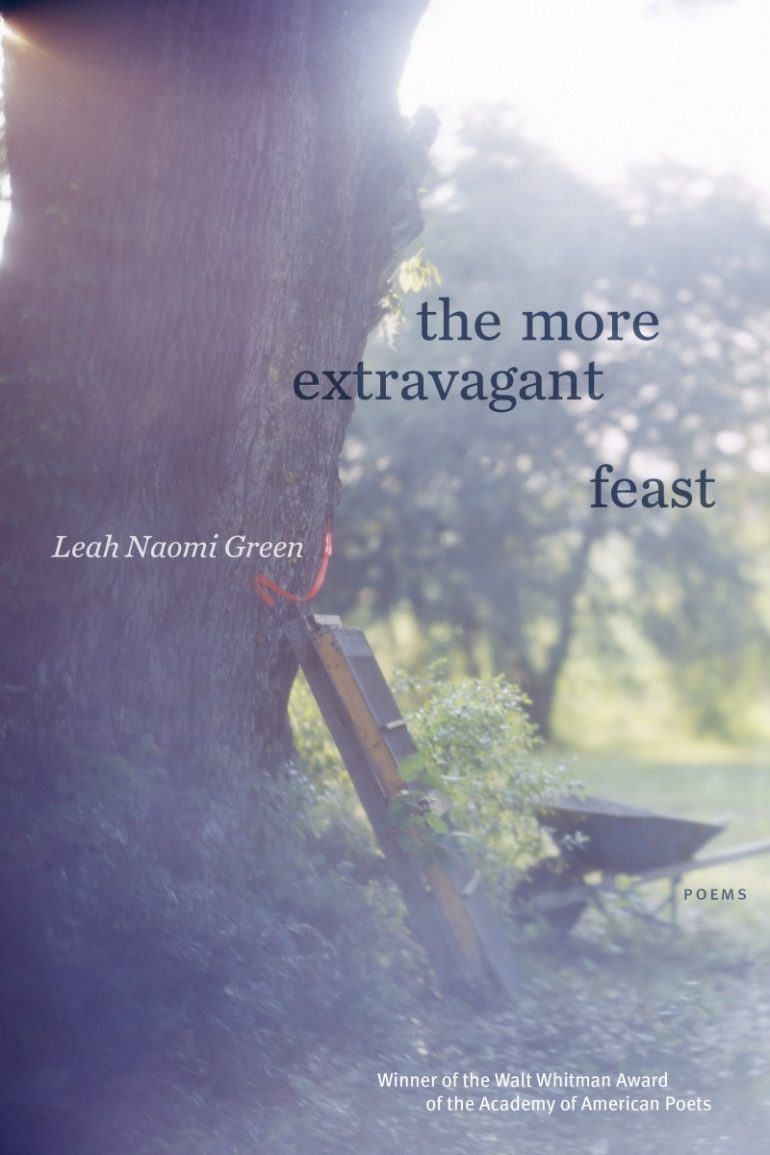

The world, held inside another world. This interconnectedness is at the core of Leah Green’s collection: “held together by holding, / by not holding.” Where does one begin and another end? Does the mother begin with the child, or the child with the mother?

This interconnectedness is also an echo of the current world. Today, we are all “holding, by not holding.” In writing this review, I want to highlight its brilliance. I want to, despite how hard it has been to write coherent sentences this year. So I will highlight a few things and then I hope people will read the collection.

A large concern of these poems is pregnancy. Writing about pregnancy in terms of time is also writing about timelessness. About time as holding and not holding. About the body’s devotion and disregard. About astonishment: the echo of the mother and child in nature, both helpless in the presence and absence of the other. Green demarcates time by gestational weeks scattered throughout the collection, as though time is slippery and unwilling to be held. And yet—.

While time escapes definition, Green’s poems are unsparing: death is as present as birth. These concepts are interdependent. A deer will die. Its body will nourish the soil & the human who eats it: “a thing, alive, becoming my own body,” much like a fetus eats of its mother. The soil will produce food and flowers from seed. This overlying metaphor threads the collection: the exterior landscape as mirror for the interior landscape. As harsh as this physical landscape is to navigate, Green’s poems are restrained as though the speaker is resigned to the natural order of things, regardless of the aftereffects.

This restraint is evident in image and line length. Every line is spare. Each image is immaculate. There is very little time for sentimentality, yet the short line stops the reader short and holds us there, time be damned. The environment is fraught. One must kill to eat. One must procreate to continue. This includes all manner of life. The moon is a prevalent image, as it often is in literature concerning women and pregnancy, but Green’s moon is as stripped down as the lines themselves, “full to term and caught / without her skin,” suggesting vulnerability to internal and external forces. But the moon is also used as reflection /mirror / light. Mother and child: one body, shuttered inside the other.

I find it interesting, after writing a collection about pregnancy myself, that we both used the word “fugue” when writing about birth and after-birth, as Green does in the first two section titles: a state or period of loss of one’s identity, often coupled with flight from one’s usual environment (Oxford). I wonder if this is an extension of reaching for explanation for the unexplainable, a name for the unnameable. A way of being in a changed world. Perhaps because one doesn’t have access to oneself. Perhaps because one doesn’t recognize oneself in this new environment. So, instead, as Green’s speaker does, one names concrete, recognizable things: “pistil, stamen, bee,” as a stabilizing act.

But I digress.

As these poems move from fugue toward the more extravagant feast, histories are carried forth through birth and rebirth. A woman’s body is the site where the past meets the future. All hope converges into “small clothes / hung on the line waiting.” Again, the “miracle” of life and death with “no idea how it is done / even as it is done.” The wonder of these poems is that they constantly reach as though wanting an answer to the unanswerable, yet they don’t strain when they don’t get one. Uncertainty is met with restraint. With spiritual and scientific arguments. With the complicated arguments of the body. The meal is an aside: it is representative of the continued survival of humans, but also gluttony and spectacle and violence. Much like childbirth, in some ways. Here, the poems shift from long lines and expensive images, to short lines that halt time. The body is the miracle, “containing the world.” Unlike love or belief or tenderness, the body is the thing that holds. That continues to hold / by not holding. That gives and gives and gives, even in death.

The enduring beauty here, then: the line, held by the poem. The binding of a book holding poems so tender that the heart might be the knife that skinned the moon.