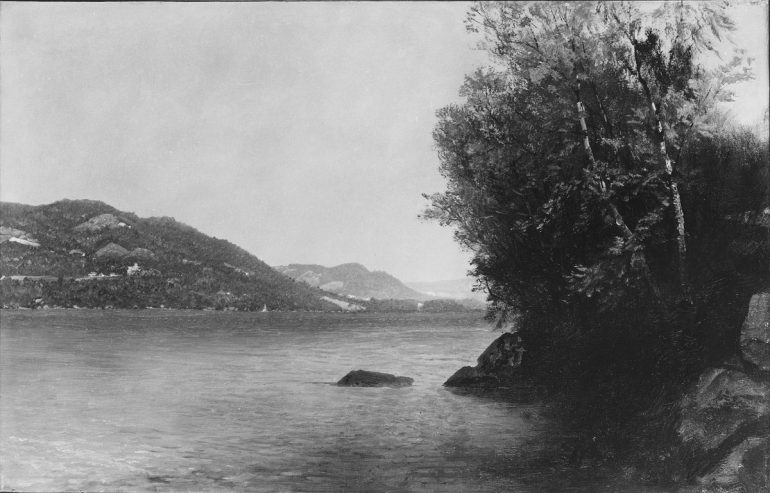

I stood waiting for Father all afternoon; watching the sun sink down, turning purple, and the lakeshore shimmering in the afterglow. Swallowed up by the night, I listened to the waters lapping on the sand, the smooth rocks, and finally I left my spot and followed the specks of light and clanking pots back to the tree-line. Mother and Winona were there by the tent cooking dinner over a small fire.

“He’s disappeared,” I told them.

Winona looked at me; rather, looked at the dark around me. She’d been staring at the fire so long she couldn’t see well. She said, “You were supposed to stay on the beach and wait for him. How will he find his way back now?”

“He’ll see the fire,” Mother soothed. She brought a spoonful of the soup up to her lips and blew on it. Winona frowned at me; she had spotted me after all.

I went down and sat cross-legged on the rocks, a short distance from the fire — close enough to feel its hot breath on my back like the whisper of a law. The forest’s sounds were coming out; low crickets looking for each other in the chilly night, birds fluttering, small creatures stumbling around and crunching leaves, hoping to not be heard. I sat there wondering if Winona was right, if my leaving the shoreline meant that Father would be trapped in his little boat on the black water of the lake, looking for me and me not being there. Mother didn’t seem too worried though; she stirred the umber soup, occasionally tasted it, and hummed soft breaths of song into the dark. Occasionally I recognized a verse or two from my nursing years, when she had held me close to her in the garden while Winona played. I had always been the younger. The round stones were cool on my uncovered legs. They were the remnants of great boulders in a river that had once run here, made small and smooth by the slow motion of the years. Someday, they might be sand; when the pines became as tall as the mountain was. Now the river was all dried up, and the landscape was changing. This is why I was concerned for Father; I feared that the lake might transform this night, catching him inside of the whirlpool and deciding, once and for all, that he should disappear. This was something that I heard him and Mother speaking of in quiet tones one night, when they both thought that we had gone to bed — him disappearing.

The night on the shore was calm. Closing my eyes, I imagined there was a wind; a cold wind that swept this place and bent the trees and the grasses in the shadows of the trees, that licked the waters and turned them white with chop. It had been that way when we were very young, with dark clouds swirling and thunder clapping out across the water, lit occasionally by flashes in the heavens. I recall great storms reshaping the horizon and changing the color of the lake and sky, and murmurs from beneath the water. There had used to be snow on the mountain, too, but it had melted in the thick years of my adolescence. This evening, the shore was tranquil; small insects lit the forest with blinking lights and glided down to skim the water, flying up then to paste themselves somewhere in the chilly sky. Sometimes they lit on me and I had to shoo them with my hand; they were new to me, and I didn’t understand them yet.

Mother said my name and I looked over to her. The fire threw its orange glow upon her and in the light she looked like some sort of goblin, well-meaning and kind but not someone that I recognized; I hoped that she was not transforming too. On a whim I made the decision that I should trust nobody ever in my life.

“Wear a blanket, will you girls?”

Winona went and put her back against a tree a small way off. Mother said the blessing and we ate dinner and then we sat a while longer by the fire, and by the time we went to bed Father, still, had not returned.

In the early hours of that night, I dreamt of the old days in the garden. I saw again the sun rising over the hedge and thickets, the hand of God peeling back the night like the skin off a fruit, and the animals awakening and setting to their work. The rabbits digging, the old foxes schooling their cubs in looking for the rabbits. And because it was the fox’s job to eat the rabbits, the rabbits had learned to live beneath the ground; they made big warrens, dark and hugging in on them as they raised their families underneath the world. Likewise, one day it had become my family’s job to leave, so we no longer saw the garden or the river there or the young fox cubs, their warm fur slicked with blood.

It was the cold that woke me; the fire had died. I sat up slowly in the place where I had fallen asleep and I felt the sting of pebbles pressing into my legs like sparks of static electricity, and for just a moment I didn’t recognize the landscape. Part of me was still in that other place, the heaven of the past, lost now except for stories, impossible to retrieve. Then my eyes adjusted to the dark, and I could see Winona laying on her own on the needle-carpet shoreline of the forest. I remembered Father, then, and I looked out at the lake reflecting one thousand stars on its blue, still surface; the changing world had not disrupted it tonight. Quietly, I stood.

I left Winona sleeping by the black bones of the fire and began to pick my way, barefoot and careful, down the slope into the forest path to go and find our father. There were no clouds and so I let the bright, full moon guide me, and the way was easy because I knew the lakeland well, as if it were a piece of me. I jumped from stone to stone and they were smooth on my bare feet, made so by the water running over them for years and years and years, more years than I had been alive. Carefully, I made my way into the trees, and suddenly it grew darker, and I was less certain of my footfalls as I tip-toed in among the dry needles that the trees had shed. It was the trees that I did not trust; they made noises in the wind, and when I closed my eyes I could imagine them coming, one by one, to life. Often I dreamed of a tree that moved like an old man in pursuit of me as I fled the woods, its rotten fruit filling the air with a thick musk and its mouth gaping like a pit from which there was no escape. When these dreams plagued me, Father would come and sit with me, and he would listen as I named my fears and he would kiss my head and tell me that everything would be alright. It was for this reason that I had left the comfort of the shore, rather than coaxing the fire and going back to sleep: if Father were to be afraid tonight, I wanted to be there so that I might comfort him. I could not bear to leave him lost on the lakeshore somewhere, all alone.

The moonlight grew fainter as I picked my way along the slowly twisting path. I passed nests of sleeping birds, the small hatchlings wrapped in the protective feathers of their parents. I passed the doors to rabbit warrens and squirrel nests in the crotch of branches, and the lightning bugs continued to blink around me like fires dying and being reborn. When the path turned back to hug the lakeshore, I left the curtain of the forest and stepped out onto the cool stones again, in the full light of the moon. At my feet just a little ways off, I noticed a pile of clothes set carefully on a rock to keep them from the creeping sand, and for a moment I puzzled over them until I heard the soft splashing from the lake and held my hand up to block the light so that I might see the water. There I witnessed Mother, beautiful in her nakedness unlike I had ever seen her, her white skin glowing in the moonlight and shimmering as the water slipped along her body and ran down her like she was made of stone. Her eyes were closed and I wondered what, in her mind, she was seeing as she rose out of the cold water like an angel and breathed deeply of the mountain air. She stood in the water up to her waist to let the moonlight color her, and then she turned and went beneath the surface again, allowing the lake to permeate her, to become a part of her soul. When she emerged, her breath escaped her lips and rose in misty clouds to join the stars.

Then very slowly the big moon slipped behind the blanket of a thunderhead, and as the shadows darkened the lake I watched her slowly cover herself, her long arms wrapping to embrace her breasts and her stomach, and I could not decide if she had suddenly grown cold or if her boldness had deserted her, and if she was again embarrassed of her nakedness, although she was alone. She stood sunken to her hips in the deep blue water and held herself against the watchful eyes of the thousand stars, her tough skin appearing soft and fallible, sinfully exposed. I slipped back into the shadows of the forest.

Then it grew cold, and I found myself among the gloomiest trees of the forest, wet with evening dew and moaning in the gentlest of breezes. I thought of Winona sleeping soundly by the grave of the old fire; she alone possessed the good ethics to sleep the night. I hoped that Mother would return before Winona woke, and they could bring the fire back to life to dry my mother’s wet hair as they sat and waited for me to return, with Father by my side. The thick clouds ate the moon, like good getting swallowed up by evil.

It was some time later that I found Father sitting by his own fire some distance from the place he had pulled his little rowboat to the rocky shore. His fishing net lay in a heap beside the boat and two fish were drying on the rocks, silver scales reflecting starlight, their long days finally done.

When Father looked up and saw me standing among the branches of the woods, a worn smile stretched his face. He said, “Hello, Faith,” and waved me over to the fire. I approached and joined him, and he touched my head affectionately as I leaned into him and toward the fire, wanting warmth and love and family. For a long time, we sat in silence, warming ourselves on the dancing flames that occasionally sent sparks floating up toward heaven. Father’s eyes were haunted as he stared into the embers. When I grew hungry, I reached into the folds of my dress to find some bread that I had saved from supper; I bit into the crust and offered the rest of it to Father. At first, he would not take it; he regarded me mistrustfully, as if I was offering a gift concealing poison.

He smiled softly. “When you grow up, you’ll look just like your mother,” he said, and took the bread from me. “You’ll have her eyes, her voice — you’ll be just like her.” “I hope you’re right,” I told him. “She is so beautiful.”

Father nodded and looked out at the lake.

“When you grow up—” he said, “—do you know what it is, to grow up?” I nodded; Winona had told me. Someday I would be as old as the mountain, or even older.

“When you grow up,” he said, “you will be just like your mother, and all of this will be hard to remember. I have no memory of being young.” He looked at me, the orange light dancing on his face. “Of being a child. I hope you can remember it happily.”

“I will,” I promised. I told him about the animals that I had seen along the path when I had come here, the birds and squirrels and the little lightening bugs. “What are they called?” I asked him.

His expression didn’t change. He answered, “I can’t remember, Faith. I used to know the name of every animal, but it has been so long.”

I thought then to ask him what he was doing here — on the wrong side of the lake with his fish spread out to dry and his net in one big tangle, as if he didn’t care for it any longer — but before I could begin, he started speaking softly to me, and I knew that I was meant to listen.

Father said, “You know, your mother and I left home before you girls were old enough to really know it. You would have loved it there. I remember it perfectly; it was a beautiful place to be born. I remember tending the garden with your mother, the sunshine, the orchards…”

Thunder born from the dark clouds shook the forest, and I took Father’s hand because I was afraid. He watched the sky with a stone face and whispered into my hair, it is alright Faith, do not be afraid. For a moment it felt as though we were not alone there in the dark refuge of the forest, and that the thunder was the voice of another party who had known my father far longer years than I had even known the world. It rumbled, digested by the atmosphere and tempered by the blue depths of the lake, and dissipated. The harbinger of the storm seemed to weigh on Father, because he squeezed my hand a little tighter and leaned ahead to stoke the fire. His palms were coarse from the years of working with his hands, and I imagined one day that mine might grow to match them, being as I was the bone of his bone, and the skin of his skin. Father said, “Your mother and I bring you girls here because we want you to understand it all; we came from the water, you know; and from the dust, and the ash. Now we are the masters over it. You girls must learn to tend the garden.”

I nodded, although I did not understand. My thoughts in those moments all had to do with my journey there to find him, and the pride I felt at having rescued him, lost as he was on the wrong side of the lake. I had been afraid to venture in among the trees but I had emerged untouched and no longer slow with apprehension. That evening I understood little of what I was being shown, but it did not occur to me to press the matter. All my universe was contained within the glow of our small fire, its warmth embracing us, nursing us, filling us with life. We were the fruits on the branch of the world.

Father told me to go on back ahead of him. I wanted to go out in the boat with him, to slip out onto the deep blue water and to float along the reflection of the sky, somewhere poised between the stars and God; but he was anxious for the storm, and he sent me back along the path alone. I left him there, by our sweet little fire, his fractured body dark in silhouette and concealing the light I knew to be inside him, placed there compassionately by a titan.

I entered the more ancient part of the forest, trees thick with the many years, and there I encountered a serpent; its eyes burned like embers in the darkness and it moved along the ground like a stream of water running between stone. I stepped away from it because my father had told me of the snakes that had lived inside the garden, but then another moment it seemed to me an old friend, a companion with a shared past who, like my father, no longer understood its purpose in the world. If he could be born again, perhaps my father would become a snake, a constrictor that could hug a thing so tightly that the creature’s heart just stopped. I felt in that night that my heart might stop from loving him so.

So I stood to watch, and the old serpent passed me by with little more than a glance and a shake of its tail before it continued on and wound down into the darkness. I emerged, finally, on the cold shore of the lake to find my mother’s wet hair and salty tears dried beside the fire, and it was not until I looked into her eyes that I understood that my father was not lost — he was leaving. And I realized then that my father would not be there when I woke up; that he would likely pass this night on the far side of the lake and then set off alone up and over the snowy mountain, because of something that I would never, even if I should live to be a thousand, understand. I thought to turn back then, to rush to find him and to take his hand to keep him here, or at least to warn him of the snake that would surely find him in the darkness, moving as it was so stealthily on the carpet of the earth, the dirt from which my whole family had arisen. And perhaps when they encountered one another on the lakeshore there, they would not regard each other as old friends, but instead as a fox and a rabbit, meeting accidentally years beyond their chapter, the two ends to an old story that would never be at peace. But instead of turning back, I went to tend the fire; my fire; the burning, wild, and always thirsty great rhetorical mystery that was the fruit of my soul.

As I understand it, I will die someday. My father told me this as we sat together that long night and looked into the fire, but he was unclear about what would happen next. I wonder about it still: did he not know, even then? Had God not told him? Nobody has told me yet, and so I make up stories of my own. I like to imagine that I might drift off and awake to find myself on that rocky shore again, on that cool night when the full moon filled the world with white divinity, and like my mother I might shed my humility and sink below the surface of the universe, and finally find the answers.