Dialogues with Rising Tides testifies to how we are inextricably intertwined in a web of ecological disaster, intergenerational trauma, and a persistent murmuring chorus of our own underlying fears and anxieties. Agodon treats these many strands with poems that are sharp with biting and self-deprecating humor yet tender with care and intimacy. By reckoning with the uncontrollable ebb and flow of life itself, this collection converses with the self, the reader, and the world at large in an attempt at cataloging loss in order to come to terms with it. “Hesitation Waltz” serves as a thesis of sorts, gliding us through these anxieties of sudden disappearances and unknowns. The speaker admits, “The hesitation is all my life I keep waiting,” then recognizes, “The hesitation is maybe life is a cobweb, / not an organizational chart.” The world defies easy categorization and description, with even the most gorgeous flowers signaling potential disaster. A “cemetery of white lilies” and “a catastrophe of white orchids” are obstacles for the speaker, who must decide to navigate this field despite the danger.

Embracing this ambitious undertaking of moving with constant threat, many poems ground themselves in the quotidian despite the overwhelming state of the world, the universe, and fate. In “String Theory Relationships,” composed in long, sinuous couplets, the speaker reminds us of an uncontrollable interconnectedness through the big bang, which brought about the formation of the universe. The speaker’s movement between the small things like “the flashlight you keep / by the door never works in emergencies” or “the woman you dislike who teaches spin class” and theoretical concepts reduces to the simple fact of interdependence and even nonimportance in the grand scheme of the universe. The speaker reminds us:

We can’t always be pretty.

We can’t always be the eyelash and the wink, sometimes we have to be

the ear, sometimes the mouth. You are and are not the speaker in this story—-

you are the bridge connected to the land connected to the man

you love […]

Here, Agodon’s work breaks the surface of everyday living to reveal a vast, seething ocean of life, forging the manmade and sometimes artificial rhythms for that which exceeds us. Some poems use humor to confront that overwhelming feeling. For example, in equal parts humor and worry, while being pitched a new vibrator the saleslady claims is Oprah recommended, the speaker in “To Help with Climate Change, We Buy Rechargeable Sex Toys” wanders towards “a feather tickler from the bargain bin,” where the train of thought soon leads to “[…] the decline of North American birds, three billion birds / missing and how each year fewer cliff swallows return / to our neighborhood.” In this collection, even the promise of momentary human pleasure can spiral into examining the costs the rest of the world must pay.

That this life is precious and precarious is central to Dialogues with Rising Tides, as Agodon uncovers familial trauma through a history of suicide, an impulse toward self-annhiliation. Nodding to the aubade, “How Damage Can Lead to Poetry,” in which the title is drawn from a note someone had written in the speaker’s book, contemplates the morning and the reverberations of language, yet this all somehow leads back to damage. “It’s morning and there’s a whisper in my family / history—-I know the suicides, the stories / of strange deaths,” the speaker confesses, delving into the harsh juxtaposition between life and death:

Even though I wasn’t there, I still see my sisters

finding our father’s first wife in the greenhouse

where he grew orchids—-jacket pocket

—-a gunshot to her head.

The tragic image of the dead in the family continues to haunt the collection, but not without a measure of care and reverence from the speaker. In “To Have and Have Not,” even as the spectre of the wife in the orchid room reappears, the speaker performs a kind of exorcism: “we scrub the blood away, untie the noose, / we keep on caring for our ghosts.” While there is an impulse to both lean toward accumulated loss in these poems, there is also the desire to continue forward, even with larger destructive forces at play.

The planet itself comes to bear the brunt of this destruction burden. While the popularized terms for our current era of “Anthropocene” or “sixth mass extinction” are never explicitly invoked in this collection, the poems still enact rapid change and loss. There is no doubt that the world and its many worlds within it are in jeopardy in Dialogues with Rising Tides. For example, in “Unsustainable,” the speaker’s thoughts jump from the occasion of a broken recycle bin to all of the plastics inhabiting the world’s oceans: “I want to keep you in my plastic / Happy Meal heart, but what snaps open // stays on earth forever,” its permanence leading to destruction. But even with all that guilt, the speaker continues accumulating more, admitting, “It hurts to say my convenience is more important / than the sea.” In similar fashion, the speaker in “At Times My Body Leans Toward Loss” has difficulty separating beauty and delight from death, even in everyday actions and life:

like the day was sun-filled but what I saw

was how I bumped the planter of Gerber daisies

and the moth fluttered up into the beak of a bird.

Death and dinner. A minor accident and something dies.

The speaker attempts to carry a global guilt that leans toward near-nihilism that, while similar across the collection, is always a variation on a theme, approached from a slightly different angle. Using brief cascading lists within its large stanzas, “Till Death Shatters the Fabulous Stars” merges memory and the flora and fauna that exist on the planet with self-destruction. Yet there is a clarity to these memories, as the speaker views them in the new light of an inevitable end, which leads to a greater reverence of the present moment, almost zen-like in its quality. Even the speaker admits, “For the last year I’ve wanted to undo everything, / unsew the haze from my eyelids—-you are here to be / swallowed up. Open the window, let the stars burn.” These lines feel distinct from pure pessimism and instead move toward a struggle to resist what may seem hopeless.

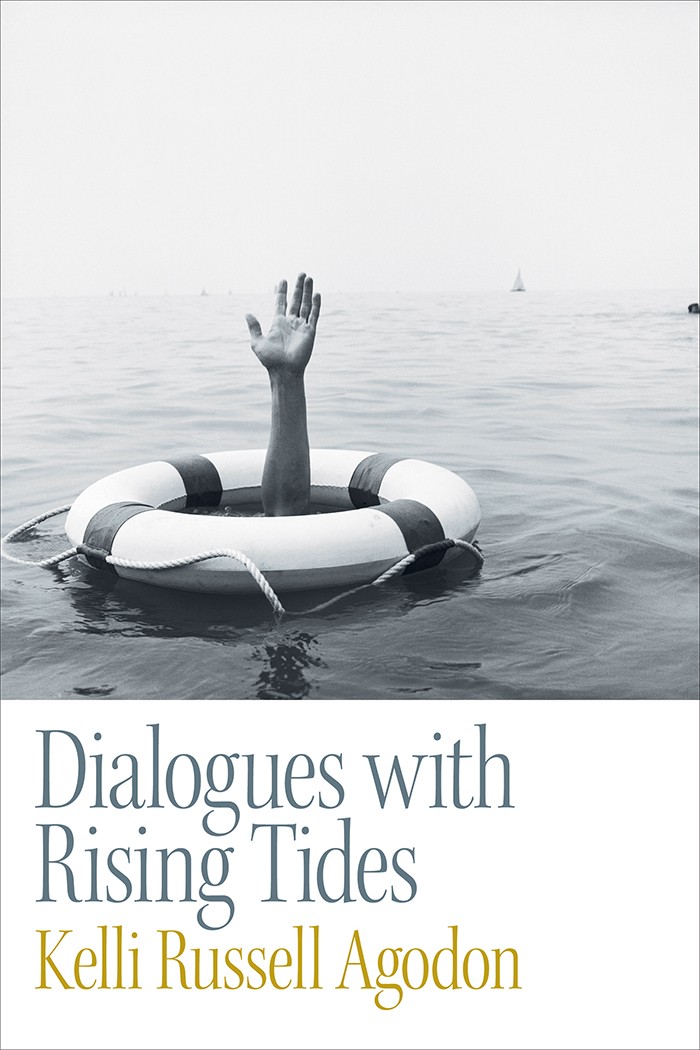

The collection progresses into this more hopeful note through its own rich metaphorical landscape of ocean to illustrate the human condition. In “SOS,” Agodon uses the shipwrecked to show a desire to move out of disaster: “our reflections are employed by the waves / as if disaster were our business, as if we’re not / wildly waving our distress flag / from the edge of this eroding shore.” While the forecast may seem dismal, like the shipwrecked crew seeking escape, Agodon still signals toward hope, buoyed by the impulse to persist. The collection’s concluding poem, “Thank You for Saving Me, Someday I’ll Save You Too,” ends in morse code given through a lost sparrow’s beating wings that translates to “Follow me into the light.” Even with its apocalyptic imagery of burning and destruction, there is the desire to turn toward something greater, to keep on surviving. Dialogues with Rising Tides is both the cautionary light from the ship as well as the flares lit up for the ship to be found, a signal to be acknowledged and rescued.