In Wildness

Woodland

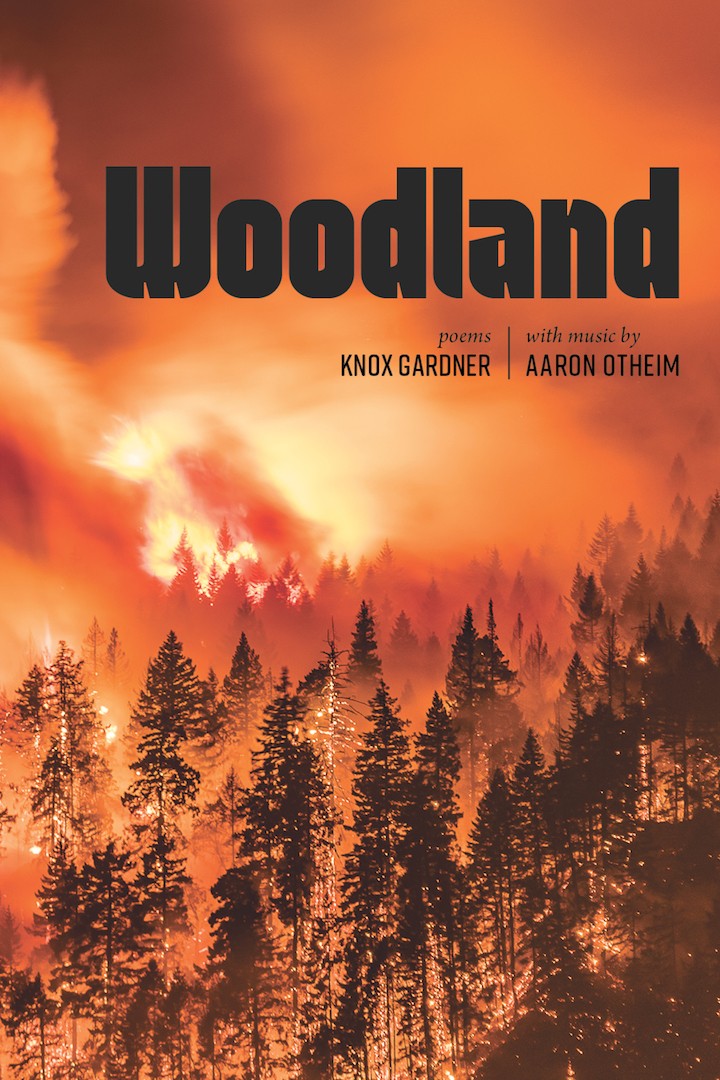

Woodland, the first full-length book of poetry by Knox Gardner, publisher and editor of Entre Ríos Books, exemplifies the vision of Entre Ríos to publish “collaborations between poets and artists of all types.” Woodland is more than poetry—it is a collaborative visual, poetic and musical response to environmental fires as well as the artistic fire between Gardner and musician Aaron Otheim. Think Susan Howe to the nth degree, as Woodland does not work with an existent library so much as create its own burning archive. Woodland is a text inseparable from fire, beginning with its cover photograph of the “Eagle Creek Fire Burning in the Columbia River Gorge on September 4, 2017,” which shows the dark silhouettes of pine trees eclipsed by orange flames. Turning the cover, the first French fold notes that the book was “started during the early season fires of 2017 in British Columbia, written that burning year, and finished as the Camp Fire obliterated Paradise, California.” The fold also notes that the text, “includes a new ‘score’ by keyboardist Aaron Otheim. Burning the 19th-century parlor music of Edward MacDowell’s Woodland Sketches, Otheim fractures the recognizable melodies of this arch-romantic work with both studio and post-recording manipulation to create a startling and darkly timbred composition.” Fire, then, is at the core of the book’s conception, both in subject and in terms of creating new music from what has been scorched. After the first French fold, two black, facing pages with white, capitalized font and the words: THIS IS A BOOK ABOUT FIRE. Turning the page, a smoky, ghostly image of Columbia River Gorge photograph appears in reverse. Fire is visually everywhere in the book—the reader cannot escape its visual heat, the drowning movement of the flames, the visual terror (and sublimity, in the Romantic sense) of the images, as on the first section page of “DENDRO.” Woodland risks being large, in its conception and execution; it risks being specific in its tenderness; it risks romanticism with its vocative “O.” The book also risks needing gallery space—the poems and the photographs of the burned music score hung on the walls, Otheim’s music and Gardner’s lilting vocals playing in the background. Woodland walks a delicate line between apparatuses of sound, image and information, but it also asks its reader to consider what they would risk for this one (tenuously) habitable world: “Were you the extravagant match, / the field of slander sticks?” a section in “DENDRO” queries. The section wonders (a significant word for Woodland, along with awe): O tinder, such a staggered palmistry the way one cups a flame in the roaring wind. The chimes unbalance the filling sky, how it pelts us with sorrows so empty without us — without our fanning worry. I was that field when I heard the striking. Such lines as those above create an evocation, a mood, a song. The reader cannot always place themselves in them, but that seems part of the point—that the lines unsettle how we look at the world, how we feel it, move our bodies in it. One section in Woodland that especially resists abstraction is a curated list of burnings around the world, titled simply “SOME BURNING: 2017.” A date, a place, and a brief description accompany each line, for example: “Jan 02 Chile Fire Destroys Homes above Chilean Port City,” or, “March 11 Kenya Fire Destroys 50 Hectares of Menengai Forest.” The list includes evacuations, arson, the death of firefighters, forest and urban fires, wildfires. The neatly ordered list is five pages long, and to read every item is an exercise for the conscience, extending the scope of Woodland to include the burning world and its many fire-related injuries and home/forest loss. “Some Burning: 2017” is an absolutely sobering element of Woodland, and demonstrates how empathy can be the outcome of a project of attention to data at a global level. The poem, “ONE: A WILD TENDER” from the WOODLAND section, captures both the speaker’s love for their subject and an attention to sound at the level of syllable. The sonics are evocative of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ delight in sprung-rhythm and hyphenated compounds, or Susan Howe’s love for the ordering of the monosyllable: wild roses stern- hipped — fieldfare field-edged & clamber O pinch scarlet, this giving let (( pleasing immemorial tho what I said was just this once always shifted always The poem’s closing sections continues: & so loved the mortar of this world ( flakes ) to be unheld — accursed & lo & lo teeters ( the cart ) A primary tension in Woodland comes from the presence of the dramatic visuals—for example: the scorched pages of MacDowell’s “To a Wild Rose”—interspersed with Gardner’s compressed, tender lyrics. The speaker is in love with the world, and is angry and grieving in the context of that love. Aaron Otheim’s piano accompaniment trills and haunts, jars and discords as Gardner’s lyric absorbs both the beauty and loss of the burned texts and the burning earth. “No tender / no hold,” a couplet reminds the reader in Woodland’s third section, “HARD CLIMATE NEVER,” playing on the homophones of tender and tinder: soft touch and flammable substance. The fourth section of Woodland, THE ROOF IS ON FIRE, is a lyric essay—one that provides context for Woodland’s visual-poetic project rather than a conclusion. In this essay, Gardner gives an account of himself as a forestry-student-turned poet, as a queer writer and thinker, as a person waking up one September morning in Seattle, “to soot pelting me…to find our entire house filled with forests from hundreds of miles away…I understood then I’d been writing about fire all summer.” The focused attention of Gardner’s essay is a radically vulnerable gift in terms of the threads it pursues and how it wonders about the speaker’s world and its making/unmaking. Gardner writes:I often think there is a seam in queer writing, particularly in the way we write about the landscape. A site angle and distancing that reflects our initial distrust of the body and its longings, not the things we learn ourselves which make our lyric and erotic poetry so compelling, but a fracture in actual corporeality and solidity of things we have somehow wronged by our being. The world itself there, a solid block rubbed smooth by others and completely baffling.

The vision of Gardner’s work, from his poetry to his editing and curating of other artists, is one rooted in ethical contexts, in shared language and shared earth. But the seams appear, rather than disappear, as Gardner considers our divided spaces, habitats, and society. Gardner notes, “It seems as likely that…the retrenchment in fear, authoritarianism, and religion will bode badly, as it always has, for the queers…it is that fear that drives this book—its fracturing, its side glances.” Gardner’s essay shows how the violence of our language and actions (words are also deeds) pervades our life with others and our world’s climate. And yet, and yet, I want to say: look at the responsive world that Gardner’s poetry, written collaboratively with the visual and musical work of Aaron Otheim, models for us. Consider the tender/tinder; consider the fire; consider the hold readers find in the expansive project of Woodland. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]