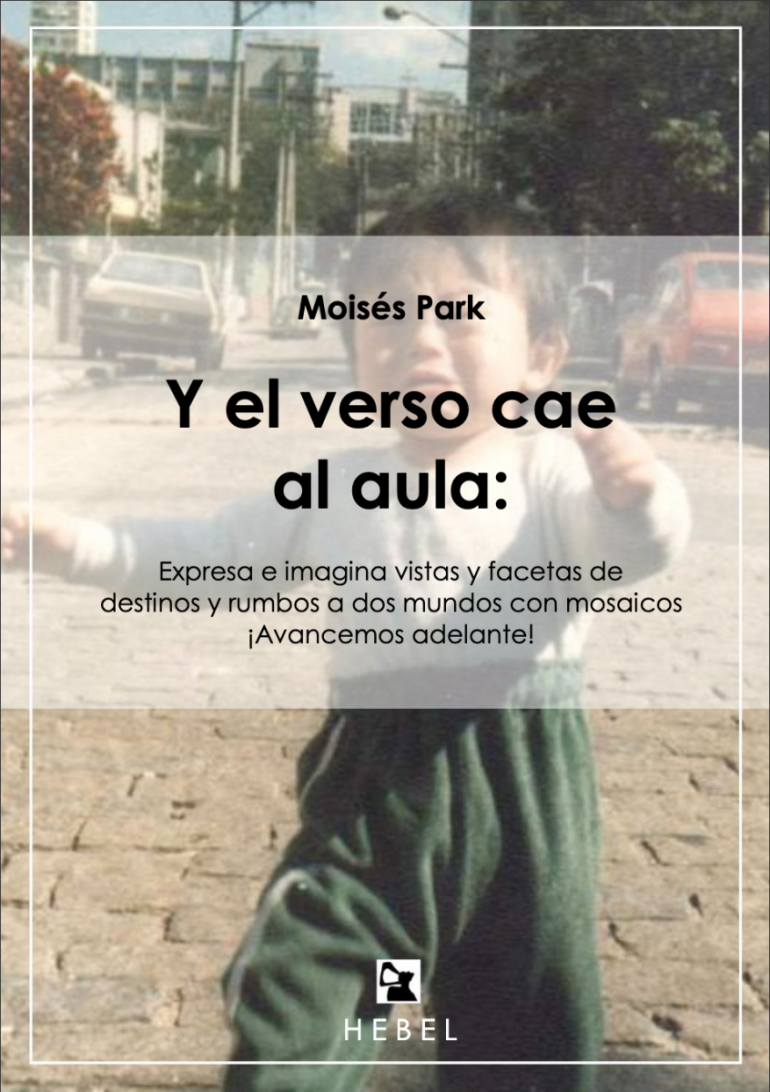

At first glance, the most noticeable thing about Y el verso cae al aula (And the verse falls into the classroom) is a picture of a crying toddler on the cover of the book, along with the subtitles that say this: Expresa e imagina vistas y facetas de destinos y rumbos a dos mundos con mosaicos (Express and imagine sights and facets of destinations and directions to two worlds with mosaics). As a Third Culture Kid (TCK), I’d always been fascinated by the idea of viewing the world through more than one lens, so the thought of contemplating “destinations and directions to two worlds” felt equally comforting and terrifying at the same time. I was excited to read more about what type of verses/poetry might fall “into the classroom,” as the title suggested, and was intrigued to know more about the concept of poetry in the classroom.

The author of the collection, Moisés Park, is a Korean-Chilean professor whose focus is Latin American language and literature, cinema, and culture. Park was born in Brazil to Korean parents whose parents had left (North) Korea before the country was officially divided into North and South Korea. Park grew up in a Palestinian-Korean neighborhood in Santiago, Chile, and spent the majority of his childhood there before immigrating to the U.S. for college. As an introduction to Y el verso cae al aula, his first poetry collection, Park states that these poems are “Frankenstein’s monster,” in that many of these poems and their creations were born out of accidental metaphors and phrases from his students in Spanish classes who erroneously mixed up phrases, used false cognates, or mispronounced words. He states that this book was originally started to essentially to help teach the Spanish language to students, but in compiling this collection of fairly humorous and lighthearted poems, Park somehow brings to light different aspects of dual identity, loss of language, and exploration of culture, oftentimes encouraging readers to dive deeper into political and social issues.

In this book, the verses act as an invitation to deconstruct ourselves as readers and get out of the classical patterns of traditional and dry grammar. The collection nudges us towards a release of language where we are pushed to expand into multiple historical, linguistic, and cultural existences. Y el verso cae al aula is divided into seven parts, each with what could be a section of a class syllabus. A few of the titles of these sections include “Grammar and Exercises,” “Vocabulary,” “Final Exams,” “Extra Credit,” and “Poetry Lessons.” The sections move through different aspects of the Spanish language, each one focusing on distinct approaches to language-learning, but also, identity-exploring.

The opening poem of the book is an abecedarian poem titled “El abecedario” in which the speaker goes through the Spanish alphabet verbally “a, be, ce, de,” etc. and constructs phrases such as “A / be / ce me canso / de ser profesor de lenguas” (19) (Let’s see, I’m tired of being a language professor) and uses homonyms and spelling errors to drive the point of “learning the alphabet” home. Instead of using what would be considered “proper” grammatical conventions, which would be “A ver, se me canso de ser profesor de lengas,” Park fits the phonetic sounds of the words in order to spell out the alphabet while still conveying the meaning of the text to the readers. In doing this, he encourages readers to think about how sounds are formed, the ways they could be perceived, and the strategies that people can use to get meaning across to others despite “grammatical” errors and mistakes.

The playfulness of creation, expression, and language extends through most of the poems, even when some of the poems deal with heavier topics and concepts, such as the dual nature of Park’s identity as a Korean-Chilean. He explores that in his poem “llamarse y llevar” (to call oneself and to carry). In this particular poem, the first stanza focuses on his name: “me llamo Moisés Park / en castellano / me llamo 박모세 / en coreano” (20). (i am called Moisés Park / in Spanish / i am called 박모세 / in korean) Park goes on to state that “Park es parque en inglés / me llaman Moises, / sin tilde / Moises es grave en inglés, Holy MOE Says” (20) (Park is Park in English / they call me Moises, / without the accent / Moises in English is serious, Holy MOE Says) and comments on the different ways people pronounce his name, depending on if he’s with Spanish speakers or English speakers. This taps into Park’s identity as a bilingual person who faces name-based microaggressions.

He also explores his last name, stating that “Park es Pérez en mi raza / somos muchos como López / Tantos Park en este mundo / mas / no es incesto” (20) (Park is like Perez in my race / there are many of us like López / There are lots of Parks in this world / but / it is not incest). This perhaps alludes to people who may have asked about his last name and made assumptions or had misconceptions about Koreans and the “lack of diversity” in last names. He then demands the reader’s attention, saying “pero atención, que no soy ni chino / soy coreano o chileno, / o combinado co-chi-le-no (o co-chi-no?)” (21) (But be careful, I am not Chinese / I am Korean or Chilean, / or combined co-chi-le-no (or co-chi-no?)). He continues, qualifying his own identity, expressing that “porque también chileno soy porque todavía digo ‘po / …porque nací en las aguas del Mapocho o en Titicaca o en Rio / …llevo sangre canutista” (21) (because I am also Chilean because I still say ‘po (a slang word specific to Chile) / … because I was born in the waters of Mapocho or in Titicaca or in Rio / … I carry Canutist blood). He then states that “me siento menos chileno / me siento más gringo ahora” (24) (I feel less Chilean / I feel more like a gringo now), talking about the ways in which he has felt his identity change over the years of having lived in the U.S. In some of his other poems, Park specifically addresses how he has had to leave behind cultural aspects of being Korean and Chilean as he has been forced to assimilate into the U.S., but continues to hold tight onto what he does have left of his two cultures from back home.

Towards the end of the poem “llamarse y llevar,” Park makes a request to his readers regarding his name and how he wants people to regard him:

“cuando muera si pudieran / cuando llame el reino eterno / cuando llegue mi partida / cuando me lleve la muerte / no me llamen Moisés Park, / ni 박모세, ni Moisé / ojalá que para entonces / olviden hasta mi nombre / mientras pisco y chicha tomen / y se coman alfajores / que haya globos y no flores” (29)

(If they could, when I die / when the eternal kingdom calls / when my departure arrives / when death takes me / do not call me Moisés Park, nor 박모세, nor Moses / hopefully by then / they’ll forget even my name / while they drink pisco and chicha / and eat alfajores (typical Chilean drinks and biscuit) / let there be balloons and no flowers)

Park emphasizes the fleeting nature of names and identity, stating that he hopes that in the end, despite the culmination of correcting people mispronouncing his name or making assumptions about him being Korean or qualifying the ways in which he’s Korean enough or Chilean enough, none of it matters. All he wants is that people will celebrate his life (with typical Chilean items) and that he is remembered by others.

In some of his other poems, such as “por y para” (“for and for” – there are two different ways of saying “for” in Spanish), he goes into a blend of political “trabalenguas” (tongue twisters): one section addresses Pinochet, a Chilean dictator under whom many innocent people were killed. The tongue twister goes like this:

“Poncio Porfirio Pol Pot Pinochet

putos porcinos poseros

poseyeron plata por pecados

¡pa’ prisión por profanos!” (54)

(Pontius Porfirio Pol Pot Pinochet

fucking poser pigs

they possessed silver for sins

prison for the profane!)

Park pairs a very lighthearted and humorous form of poetry (tongue twisters) with a serious and political theme, making readers think through the nature of what words can do to people’s perceptions of history and culture. From my experiences of having lived in Chile before, the way that many Chileans have dealt with (and continue to deal with) the atrocities that were committed during the Pinochet era is through humor. They seem to take what happened in the past, and as a way of coming to terms with the horrors of it, turned to humor as a coping mechanism, oftentimes undermining what really happened. Park captures this sentiment really well by containing this piece of political attitude in the form of a tongue twister.

In Y el verso cae al aula, Park forces readers to consider each of the poems carefully and somehow includes elements of surprise in them through a play on words and by opening up a new perspective that language can offer. The poems carry readers away, the rhythms being the guiding force behind them, and Park also incorporates pauses and silences in order to help drive specific realizations home. The collection gives people an opportunity to appreciate the metalanguage and the different levels that language can offer. One of the biggest accomplishments of this collection is that Park encourages people to express and imagine through two worlds in order to learn in the classroom and outside the classroom. Even from the subtitle of the book all the way to the end of the collection, there is a call to experiment with words, become friends with words, and confide in them—hopefully, through this collection, readers will have opportunities to add to the experimentation of language within poetry, thus continuing to create verses that explore different worlds.