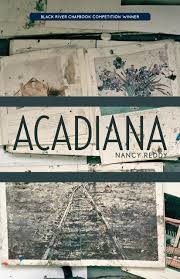

A Review of Acadiana (Black Lawrence Press) by Nancy Reddy

Writing informed by geography tends to stake two kinds of claims: the claims we make about a place, and the claims a place makes upon us. James Joyce’s response to a question about returning to Dublin - “Have I ever left?” - indicates that there are certain neighborhoods and terrains, often those inhabited during childhood and early life, that are forever present in our imaginations and our bodies, wherever we might currently be receiving mail. Nancy Reddy no longer lives in Louisiana, but she conjures the state with magical authority in her haunting, haunted chapbook Acadiana, the winner of the Black River Chapbook competition.

‘What is this raw and wind-worn place/we have survived into,’ she asks in the opening poem, “Dirge,” though the sentence ends with a period rather than question mark, as though the speaker is too exhausted to bother lifting her voice, asking whoever might have the answers. Indeed, she worries, ‘The wrong gods//roar into our lungs now.’ The poem begins with fragmentary observation of ecological catastrophe:

First the sky

broken by birds

flying at the wrong season.

In the world these poems depict, which is to say, our world, the one after Katrina and the BP oil spill, the one of the Trump administration with an EPA and Interior Secretary more suited to play Bond villains than serve as faithful stewards of nature, religion – that is, a binding again – is desperately needed. ‘I cannot tell if you are listening,’ Reddy laments in “Saint Charlene Offers Up Her Suffering,” directly addressing God, whose absence illuminates these poems like the ‘box of barnburners’ the speaker’s papa uses in “The First Miracle.” In that poem the miracle is also an act of terror, as papa burns the young girl in order to show her the way flesh recovers from a wound. It is both a crucifixion and a resurrection, ‘new skin risen opalescent beneath my worldly/flesh.’ The instructions Jesus often gave, ‘Tell no one,’ when uttered by papa at the end of the poem, are laced with shame.

While I find echoes of Sylvia Plath and Lucille Clifton in these poems, the artist I thought of most was David Lynch. Just beneath or around the corner from idyllic scenes of American innocence lurk images and acts of horrible violence. In “Signs Resembling Sacraments,” Reddy offers chilling stage directions:

Hold her under

until her hair fans

the riverbed’s darkest smoothest rocks,

until her eyes loll in their sockets

then snap open.

‘When I left her she was still unharmed,’ the last line of “Saint James at the Ascension Parish Drive-In,” in which the speaker observes a young girl passed out next to a car, leaves the reader to imagine what harm befell her. Harm is widespread in Acadiana, yet the attention Reddy gives injured and discarded women, ‘four men/lost out on a deep sea rig,’ ‘this field/pocked by detonation,’ is, as Simone Weil said attention can be, a form of prayer, and as such has the power of reclamation, redemption. Though God may be ‘just a whisper in the under/now,’ these poems give readers ears to hear.