Just as biodiversity strengthens natural systems, the diversity of human experience strengthens our conservation efforts for the benefit of nature and all human beings. Audubon must represent and reflect that human diversity, embracing it in all the communities where we work, in order to achieve our conservation goals.

Diversity & Inclusion Statement, National Audubon Society

I have always been struck by the power and beauty of biodiversity. It anchors the National Audubon Society’s Diversity & Inclusion statement because diversity is always present when nature and the planet are thriving optimally. And ideally this is the state of nature that must be conserved and sustained. We see it in healthy native plant gardens, coral reefs, in the range of bird species and among culturally rich neighborhoods and cities. But, in my training as an ecological theologian, what inspired me even more about the excellence of diverse ecosystems is the way that every entity on the planet is intrinsically connected. Sallie McFague, a leading ecological theologian and the first to read my dissertation for my doctor of philosophy, would become almost starry‐eyed and breathless when she lectured about how, “We [humans] are, literally, bone of the bone, flesh of flesh of nature. We come from it and we will return to it; and our every waking moment is dependent on the air we breathe, the water we drink, the grain we eat. This influence can be seen in telescopic and microscopic ways—in the ashes from the stars that compose the atoms in our bodies.”

I remember sitting in the lecture hall thinking, wow, this ancient, original connection to nature is so awesomely undeniable. It made me wonder why, when conservationist Rachel Carlson warned that we were subjecting ourselves to slow poisoning by the misuse of chemical pesticides that polluted the environment, we didn’t realize that we were also injecting our very bone marrow with the same fatal toxins. Whatever we do to nature, we are doing to ourselves. Yet, becoming sensitive to this connection requires people to stop seeing our relationship with nature as a subject‐object proposition, according to McFague. She argues that what is required is a subject‐subject reclaiming of our human connection with nature. She describes this connection as a spiritual ecology, which does not diminish our human quest for more subjective or personal meaning and experience between ourselves and something larger than ourselves; God or other sacred values. Seeking our authentic relationship with nature becomes a needed value in our quest for meaning.

My commitment to spiritual ecology was nurtured very early in my life by my father, a prominent civil rights activist, artist, minster, liberation theologian and seminary professor. Reconnecting me and my siblings back to nature became a vital way that he and my mother counteracted the negative impact of racism, sexism, and other negativities in society. Camping trips with my family, three months, every summer for twelve years established my passionate sensitivity toward nature. My family began these nature excursions in 1968, when I was in third grade and the civil rights movement was in a fierce struggle to make freedom, safety, confidence, and self‐acceptance an authentic reality for all black people. But, when my sister, brother, and I played in forests, dunes, meadows, beaches, deserts, and marshes we transcended the devaluing of who we were and the resulting social and physical limitations that restricted us because we were black. Our play and exploration in nature was unstructured and unchecked, and I remember feeling free, confident, safe, and natural in my skin. What helped me, and my family, integrate campsites and stand against the encounters of varying levels of racism during those summers throughout the 1970s, was a vital understanding of our mutual interdependence with everything. My father often reminded us of Psalms 24:1 “The earth is the Lord’s, and the fullness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein.” He wanted his children to not be afraid to go anywhere on the planet. And, I am not afraid and have a profound sense of being an earthling, as novelist Alice Walker proudly proclaims through The Color Purple. Walker’s character Celie, expressively captures my spiritual connection to nature when she declares, “But one day when I was sitting quiet and feeling like a motherless child, which I was, it come to me: that feeling of being part of everything, not separate at all. I knew that if I cut a tree, my arm would bleed.”

My spiritual sense of interdependence with nature drives me to raise the same question about climate change today, as I did in graduate school about the warnings from Rachel Carson. It is even more apparent today that whatever we do to nature, we are doing to ourselves. I believe that in many ways climate change is the greatest test for how we live out our faith. It is inspiring to see how faith communities are galvanizing action in the Green the Church movement, for example, where African‐American congregations are joining together to the fight against climate change and helping churches serve as centers of resilience.

For example, at Audubon, our North Carolina team is partnering with Creation Care Alliance of Western North Carolina and North Carolina Interfaith Power and Light to integrate birds into the larger conversation of creation care, heeding the moral and spiritual call to honor the integrity of God’s creation. Creation care advocates are among the growing choir of voices pushing for bipartisan political action on climate change. Spreading the word about Audubon’s groundbreaking Birds and Climate Change Report—that shows half of North American bird species are threatened by climate change during this century—with people of faith is a part of Audubon’s climate initiative plan. It’s a way to reach people who might not be Audubon or conservation engaged, but who are primed to help.

As the Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion, I help Audubon, a secular, conservation nonprofit, expand and create new partnerships with religious organizations. Religious groups are not just viewed as another diverse partner, but as faith traditions that also have important teachings about how to live in right balance and relationship with creation and the Earth—which is crucial to stopping the harmful impacts of global warming. They are primed to inspire and encourage people to embrace a deeper spiritual ecology that tells us about restraint, sharing our resources, loving all of God’s creation, and even loving our neighbors as ourselves which supports conservation action and the long term sustainability of the planet.

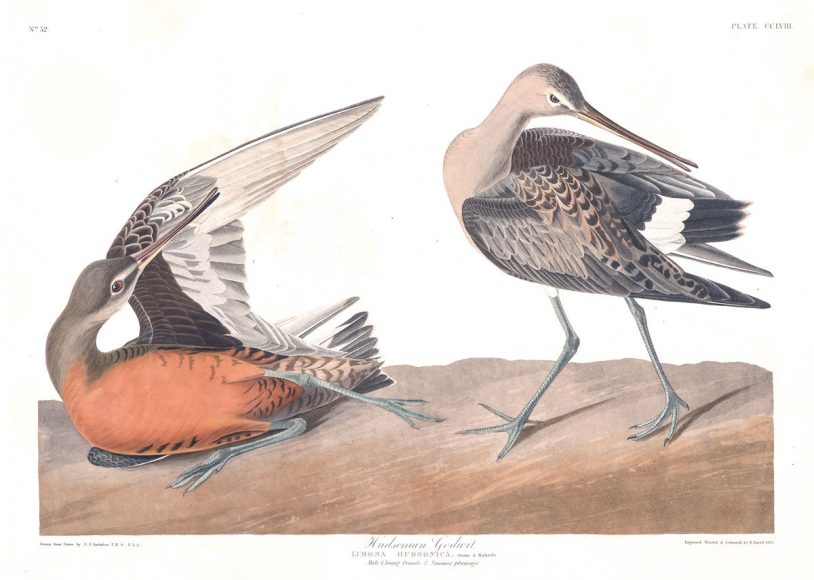

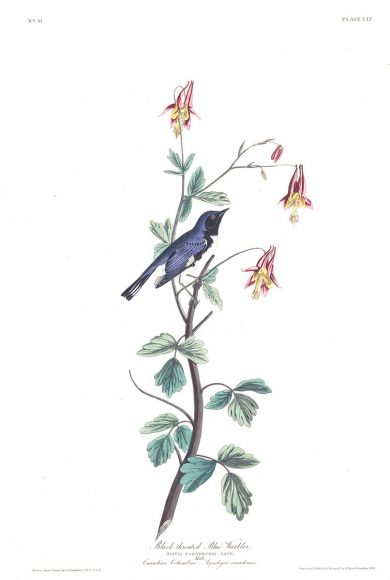

Audubon’s contribution to spiritual ecology is the awakening of the sensitivity to nature through birds. Birds are a crucial link in the chain of life. The vast distances birds travel during migration and their exposure to diverse ecosystems make them unique barometers of the Earth’s health. Moreover, birds differ in color, size, behavior, geographical preference and countless other ways and represent the beauty of biodiversity as much as they require healthy biodiverse habitats to thrive. Birds also inspire us to honor and celebrate the equally remarkable diversity of the human species and connect us to the highest value of our interdependence. As we often say at Audubon, “Where birds thrive, people prosper.”

The “godfather of biodiversity” Thomas Lovejoy says, “If you take care of the birds, you take care of most of the big problems in the world.” This is in part because even taking care of the smallest sparrow can become an act with monumental impact for bird conservation as well as for the flourishing of a spiritual ecology. Taking care of the birds helps bridge the subject‐subject connection to nature and take it beyond just a conservation practice, to becoming a deeper spiritual obligation.

The illustrations highlight the diversity of bird species threatened by human society. These ‘priority’ birds are identified by the Audubon Society as in need of our focus and conservation efforts. All illustrations are from John J. Audubon’s “Birds of America” provided by the Audubon at audubon.org/birds‐of‐america. Learn more about Audubon’s ‘priority’ birds here. Plate 250 Artic Tern, Plate 155 Black-throated Blue Warbler, Plate 258 Hudsonean Godwit, Plate 307 Blue Crane, Plate 328 Long Legged Avocet, Plate 31 White Headed (Bald) Eagle.