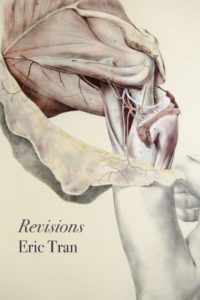

A Review of Revisions (Sibling Rivalry Press) by Eric Tran

‘empty me out,’ Eric Tran writes at the end of his gorgeous poem, “How To Pray.” Tran’s chapbook, Revisions, documents such emptyings, such prayers. In prose and lyric poems Tran, who is also a medical student, tracks the ways we heal and the ways we wound. That italicized voice at the end of “How To Pray” is, in fact, the voice of ‘a whistling, worried/kettle,’ begging ‘savior/take me off the fire.’ It reminds me of Henri Cole’s poem “My Tea Ceremony,” which leaps from the speaker’s awareness of ‘water murmuring in the kettle’ to this startling address: ‘Heart, unquiet thing,/I don’t want to hate anymore.’

Both poems connect the everyday danger (and pleasure) of a hot kettle with spiritual wisdom, the desire to be emptied of that which is damaging or that which can be more useful, more beautiful elsewhere. In Tran’s poems, heat is both warning and longing. At the end of “My Mother Asks How I Was Gay Before Sleeping With a Man” the speaker is scolded by his mother:

I warned you once not to touch red coils,

but you had to reach out, palm the heat,

hold the fire in your fist to learn your own fear.

Readers of Revisions hold fire in their hands. This is a collection that instructs us in the ways of fear, the ways of prayer, the ways of coming to terms with truths that can feel impossible to bear. The truths that Tran explores are at once deeply personal and political, emerging from his identity as a medical student and a queer man of color, a child of Vietnamese immigrants and one seeking to make a way in two, sometimes contradictory, professions. Loss and grief permeate these poems, though Tran handles such heavy materials with the deftness one would expect from a poet who is also a physician, a physician who is also a poet. ‘Redact the news,’ the speaker of the title poem implores, calling to mind the words of that earlier doctor-poet who wrote:

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

“Portraits of the Days’ Griefs” begins ‘Today’s grief and I grope the man I’ve loved while the man he’s/loved finds us coffee.’ Has grief ever been expressed with such charm, such offhand panache? There’s something about the lightness of the poem that is both winsome and deeply moving. Tran’s range of style, subject, and tone is formidable and beguiling. “Anatomy & Phys,” about a professor who raped his students, concludes with this powerful confession: ‘I’ll remember I once wanted him to pick me,/and still my blood will run hot.’ One recalls that Keats, too, hoped to become a doctor, when reading the first two lines of “Forensics Lecture After the Shooting of Michael Brown”:

This morning, a list of wounds to commit

to memory: contusion, abrasion, compound fracture.

The relationship between memory and trauma, education and seduction, pain and hope, beauty and truth — these all receive Tran’s studious, loving attention. One of my favorite poems in the collection, “The First X-Ray,” examines the accidental nature of much scientific discovery, and how something designed to injure can be transfigured into a means of recovery.

Mustard gas

fathered chemo: autopsies of blistered victims

showed tumors lulled into slumber. Wildfires

clear stagnant fields clean — eventually you

hardly remember the earth’s scarred flesh.

I live in an area known as the Lost Pines — so-called because the loblolly forest that once surrounded the town of Bastrop, Texas was an ecological anomaly, separated by more than 100 miles from tree kin that stretch from east Texas to the Atlantic coast. Fires in 2011 destroyed 34,000 acres, so now the pines truly are lost. It is difficult not to remember the earth’s scarred flesh in such a setting, yet Tran’s poetry — visionary and redemptive — gives me reason to believe in the future.