“For some…the liminal becomes their only dwelling place—becomes home”[1]

Jane Hirshfield

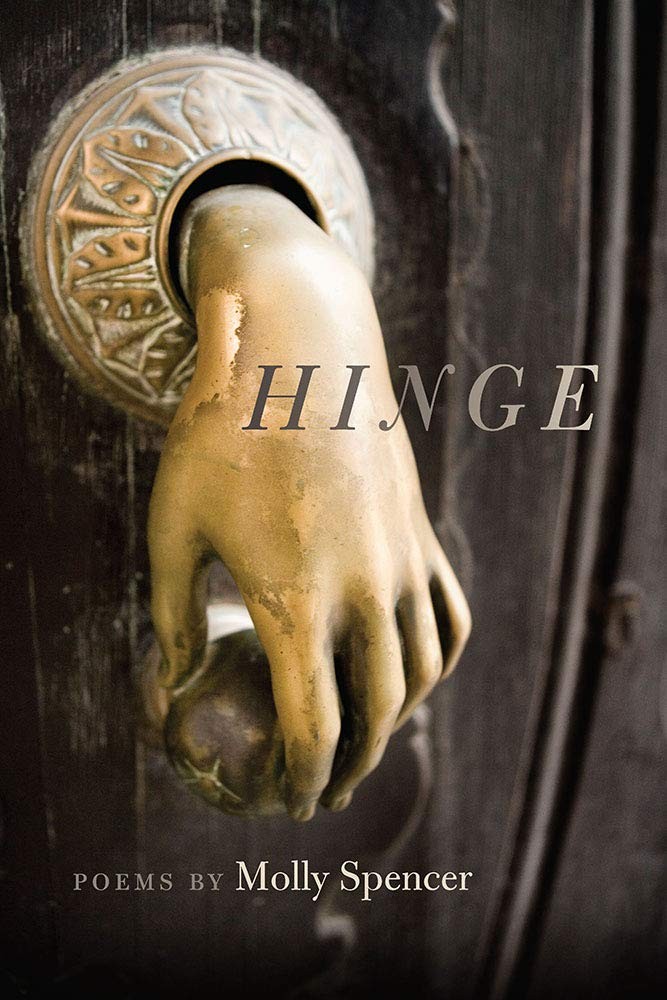

Perhaps it’s because I’ve recently crossed into midlife, the space between young and old. Perhaps because the soft babies that occupied so many years have somehow disappeared into long, angular, almost-adult creatures who can, mostly, tend to themselves. Perhaps it’s because the last four years in the United States have felt like leaning over a precipice on unstable ground. And, perhaps, it’s because my physical body is suddenly, and clearly, as temporary as a moth, a flood, a season always morphing into another season. Whatever the reason, Molly Spencer’s “Hinge” resonated deeply with how my perception of the world, and its relationship to my self, has shifted in recent years. More and more life feels like a constant flow rather than stages or fixed states of being or identity.

It’s apt that Spencer’s book opens with a flood, signaling to the reader that we’re entering the space of groundlessness—

I go down

To watch the water’s surge

and spoils—there goes our table,

there, the spare key, there go

the stories I told them.

The children are growing

long and ravenous

What can I build

That will hold?

These poems move through and past one threshold to the next, swirling between multiple social roles—girl, woman, daughter, mother, wife—as familiar fairytale and myth collide with the lived experience of girlhood, marriage, motherhood, and chronic illness. Fixed identities dissolve, morph, mingle, and give way change.

On the level of grammar, metaphor, and story each poem is an effort to build a temporary roof “from all that is fallen,” from all that keeps falling. Spencer’s enjambed lines enact this state of flux on the page. In A Little Book on Form Robert Hass describes enjambment as “being in process…instability and movement and change,”[2] a good description of both the gesture within these individual poems and the collection as a whole. In “ONSET” the speaker describes the beginning of a (as yet unnamed) chronic illness. One line tumbles into the next as the speaker’s role of mother is destabilized. Periods in the poem function more as a pause or breath than grammatically closed statements:

Late snow, and after,

the orchard tamed, unblossomed.

That waking

to a stunted world

the clock made loud

and slow.

Even as the speaker’s body is stilled by pain, the world continues to make and unmake itself around her while the self also sits in a space between mother and daughter and patient. The movement of one line to the next, without pause, reflects this inner multiplicity.

Say your mother found you

Hot and aching, wooden, warped, your bones

Made sudden by pain

Say she said, Rest, and you rested,

hearing far voices—the bodies

you’d birthed—down hallways long and bare

She said, Take this, and you took it.

Then slept. A sheet pulled tight

the whole world whitening. Sooner or later

every house has a sick room—

pale walls built by weather and waiting.

A window for weak light, the door forever ajar.

When the line functions as a proper sentence, “a proposition of finitude,”[3] it often enacts the uneasy safety of prescribed roles in a fairytale or myth, just before the world turns on its head, as in “Love Poem for Lupus”:

I’ve worn the pelt of forest shade.

I’ve worn my little hood of red.

The path is aching with thaw.

When I find the house alone in the wood,

I’m always a tender young thing.

Grandmother’s dead six years.

There is sorrow.

Birds in winter plume.

Salt for the deer to nose.

The “I” and the reader’s “eye” are both allowed a short rest in a familiar story/myth and in conventional grammar, but not without hints in the language of coming disruption—an aching path, a dead grandmother, sorrow. In the next stanza the wolf, (Lupus / illness) enters and with his entry the enjambed line, the grammar of liminal, returns—

The wolf

raised the latch and door swung wide

open years ago now. There may be a fire

with hands for flames. There may be a witch

an oven stoked. Surely a bed turned down

for me. A rug at the hearth where the wolf

sleeps. (68-69)

Spencer’s metaphors and similes also make home of in between spaces—her body is “a ransacked room,” “the dim house / the blurred threshold / between mother and creature / …ebbing,” “a warped doorway…No…a boat.” Both the physical and social selves are unmoored or obscured, evoking non-duality, constant shift, and the haunting permeability that seeps through the whole collection. Further, many images directly connect the speaker’s sense of her social self/ves and her physical body to natural processes of change and decay. More from the series poem “Patient Years” that makes up the second section of Hinge—the body is “the deep woods” and “a vague constellation of symptoms.” In “Vernal” the self and body are a sleeping meadow—“Some meadow somewhere quivers / under snow, / It may be inside you.”

“Berry” and “Basket” extend this impulse to the poem entirely. In “Basket” the speaker moves through girl, woman, mother, and/or from health to a chronic illness that comes and goes, in the guise of grass. In the first stanzas we begin as a girl and/or a healthy body.

To begin slender

in a slow river, wading

To curtain the seam

where water skims land

To come loose from your roots,

Be gathered, carried

you know not where

The next four can be read as the shift into woman, to wife, and/or appearance of illness—the self dissolving and reforming

To relinquish your long greening,

go hollow, fade

To revive in water, to soften

To sway in someone’s hands,

their kitchen

To be woven, half-done, half-

done for months, for seasons

And the final stanzas can be read as the shift to mother and/or a body learning to live with the presence of chronic illness that comes and goes, that has periods of flare and recession.

To pick up again, tender weave,

Meet yourself coming round

To be vessel, full

then empty, then full again

To bear that weight

To be bridged with a place

for holding

Spencer also remakes myth and story in order to trouble neat lines between static identities. Demeter and Persephone are threaded throughout the collection such that the speaker might be either or both mother and daughter. The myth is also connected to seasonal cycles of birth and decay. Appearing early in the collection (“Demeter, Searching”) we witness a mother’s frantic search for her missing daughter written in tercets. The third line can be read as a visual intrusion of the male and/or illness into both the relationship between and the coupled identities of daughter/mother and girl/woman. So, the poem can be read as a mother searching for her lost daughter or the speaker becoming a mother searching for her former self, for her girl self, or as the once healthy body searching for itself before illness. Once again Spencer’s gift for making the liminal home allows for many possible readings and liminality is reflected in her formal choices:

…

went home, looked under the bed.

In the stalled closet, leaved through her sleeves

For clues. Even laid myself down

On the thatched field, listening,

For the deep thud-thud

Of his headboard against the wall.

When Persephone appears in the kitchen, seemingly out of nowhere, with the laundry basket on her hip, the mother and daughter desperately work together to restore what was stolen what, ultimately, can never be restored. Also, the wonderful way the repetition of hours, hours, hours, also holds ours, ours, ours.

It was hours of scrubbing and rinsing, hours

Of pinning bleach petals of slip

And lament on the line before I asked

Where? It was hours

Before her deep-water reply: Mom,

Mom. It’s not the kind of place you can point to.

Nearing the end of the collection, in “Persephone, Midsummer,” home has become these identities in relationship and flux.

I no longer know how I came to be here.

She claimed me? He returned me?

A cleaving, more light

Than I’m used to now, then everyone pretending

I’ve never been anywhere else

here at the sink, tasting summer

In my mother’s kitchen, washing plates

Until their painted edges fad.

But I’ve taken on the green

of his river.

Spencer’s “chosen path is immersion rather than escape…and above all a radical allegiance to the non-dual.”[4] Here the speaker is, again, mother/wife/daughter having accepted the reality she moves both within the limits of and beyond those identities.

A deal I struck once—

the way I left off tending, hoping

growing things would know to dig

for what they needed

deeper down. (64)

Hinge is the world as flux made from words, images, grammars, and stories also in flux. In this way, it was the perfect read for this transitional moment in my own life. But perhaps also for the life of our country. These poems follow an individual body through the normal shifts of life, forced to reimagine foundational identities because of the complication of lived experience, including chronic illness. It is the process of one body, a white woman’s body, making her dwelling in the liminal, but these poems might offer clues for how collectively, we might do the same. In her essay “Writing and the Threshold Life,” which I’ve been quoting throughout, Jane Hirshfield asks “And what of that other work of liminality, the way the threshold existence opens into a more capacious sense of community?[5] It’s a question worth considering. As Covid makes us stop, as the white supremacist rot beneath our national myths becomes more and more apparent, as the limit and violence of socially prescribed roles become more and more clear, how do we build a home from all that is fallen, all that keeps falling? Maybe like the Hinge Molly built, where there is no easy safety, where every beauty is troubled, but there is also a quiet, attentive watching. Where each interior “I” is witness and participant in the floods that upend the illusion of statis, yet can still touch the stillness beneath the ever-flowing surface of difficulty. If each “I” in America could find the tenderness within struggle and pain, as Spencer does in her poems, I think we might find a way to find home in the inbetween, where there is space enough for all of us. Which is what, for me, makes Molly Spencer’s work remarkable and worth reading again and again.

[1] Hirshfield, Jane. Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, Essays. (New York: Harper Perennial, 1998) 208.

[2] Hass, Robert, A Little Book on Form (New York: ECCO, 2017) 11.

[3] Hass, Robert, A Little Book on Form (New York: ECCO, 2017) 11.

[4] Hirshfield, Jane. Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, Essays. (New York: Harper Perennial, 1998) 207.

[5] Hirshfield, Jane. Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, Essays. (New York: Harper Perennial, 1998) 208.