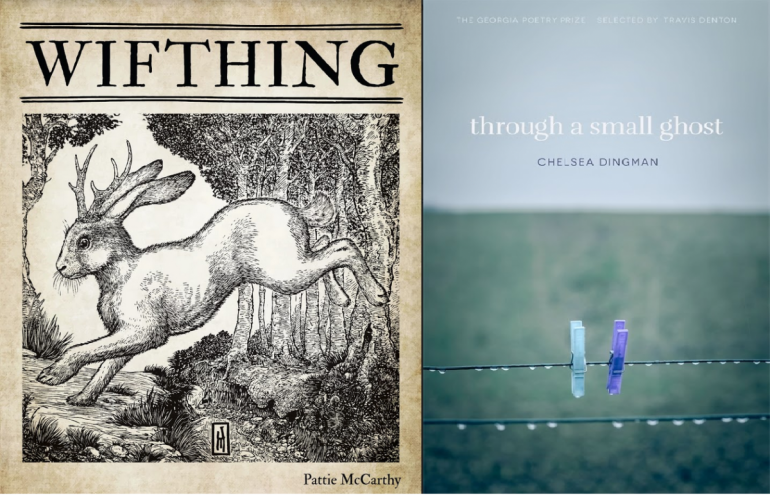

I have in front of me two collections which should shake the foundations of what a person thinks they know about conception, child loss, and pregnancy—but also women’s history, women’s medicine, women’s narratives; what lore survives the dominancy of patriarchy. Chelsea Dingman’s Through a Small Ghost (UGA, 2020) and Pattie McCarthy’s wifthing (Apogee Press, 2021) are poetry collections that embody for me what Muriel Rukeyser wrote in her homage poem for Käthe Kollwitz: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? / The world would split open.”

Through a Small Ghost by Chelsea Dingman. UGA Press, 2020. 120 pages. $19.95.

“rain is coming & coming / in the distance”

The cover of Through a Small Ghost features an image of two plastic clothespins on a rainy clothesline: a pale blue and a violet clothespin. Rain beads the line, and the background is divided between a sage green and a pale blue. There is a gentleness and a softness to the cover that I want to mention, because to think that Chelsea Dingman’s poetry will be a soft experience is like imagining rain to be always gentle, and to avoid thinking about the flashfloods, hurricanes and destruction that regularly accompany the event of rain. I remember thinking how unprepared I was for the power of Dingman’s poetry, for the violence embedded in personal narrative poetry speaking to child loss and birth. I’ve given birth—you would think I would know these things—but the way women’s narratives are forcibly framed by society (doctors, textbooks, fiction) keeps the power and the violence of women’s narratives at bay, hushes and silences, elides and covers over.

Dingman’s collection opens with the poem “Memento Mori”—a Latin title which translates to “remember your death,” a medieval concept meant to bring holy sobriety to living. In this poem, the speaker’s body is “a chapel of bones” and “the house you will forget how to breathe in.” Death and remembrance is at all the windows. “What reminder will you leave me / with?” the speaker wonders, “This sad architecture of bone & bristle / & sackcloth. This vanitas.” We have entered a ritualized space, a holy space—one weighted and biblical, yet one that also embraces the contemporary circumstances of its time: “Tell me, again,” says the speaker, “about the man who threw his daughter / from the Skyway Bridge.” There is the possibility, in Dingman’s poetry, that the world is every bit as full of violence and grief as the ancient days—that we have somehow been pretending it isn’t.

In the poem “Intersections,” the speaker watches a mare foaling in a field: “I’ve seen this before: / the way a woman’s body reaches // for its own ruin.” Every time I read this poem, I’m levelled again. These are not the terms in which birth is described to a person—who would go through with birth if they were? Dingman offers new language for thinking about the event of birth:

In the 18th century, the sacrum was believed

to be indestructible. The sacred bone.

But so much of birth is destruction—

the vertebrae, the bodies, the promontory.

Where & when & where. The intersection

of all parts. A cathedral’s bronze doors

opening. The sudden obedience

of warring states. A labour that can be

outlasted. And, sometimes, a good birth

is merely a gasp of air. Blood. Shit.

The cathedral, its windows kicked out.

The extended image is one of desecration—a holy space intentionally wrecked, blown or torn asunder. And yet, the birthing body is compared to a cathedral, a towering feat of architecture. The metaphor of civil war (“warring states”) puts birth into a narrative where birth is more physical clash than harmony, less the rhythm of contractions, and more the seizure and capture of a holy space. In the poem “Self-Portrait as God with a Stillborn Inside,” the speaker is even more explicit: “Believe me: childbirth is war. Let the blade // learn you. Let your throat soften against it. / Let the rules of war not apply.” Lines from Genesis—the creational fiats—interweave the poem: “Let there be light” and “Let the earth bring forth // living creatures after their kind.” There is agon in the wrestling between scriptural text and the speaker’s experience, and the sensation of existing in multiple spaces becomes a hallmark of reading Dingman’s the book.

Dingman’s forms often destabilize language—alternating couplet and monostich stanzas, tercets (sometimes called the most unstable stanza form), visual caesura and fragments that use the whole field of the page—as in the poem “Ephemera,” which contains a portrait of a stillborn child: “her still face, cold & closed / as we kissed it, / taught me love / is not a fence / to tether our bodies to.” Untethered language mirrors the untethered body, the body that has nothing to lose, the body in pain and grief that knows itself “So terribly / alive” by way of its own suffering. Dingman’s reader might have expected ethereal, ghostly language to be the driving imagistic force of the collection, but instead it is the earthly, elemental image of the hurricane that rises out of the pages of Through a Small Ghost. The hurricane as pure metaphor in “To the Spontaneously Aborted Fetus” (“I borrowed a hurricane / from the sky / to tell me how some storms rail / & others rally) and as ambiguous metaphor in “For Our Daughter,” bridging literal and figurative worlds: “This is what an altar / looks like, our church rent / / from the ground during a hurricane.” In the poem “When the World,” hurricane season is the Gulf Coast’s literal calendar time of storms, but of course when a poet names a literal phenomenon (in this case, storm season), metaphor enters regardless of invitation. Storms allow the speaker to address both her body and others: the intimacies of miscarriage and child loss, but also of partner. “When the World” and “Letter from the Gulf Coast” are two of a number of love poems in Through a Small Ghost that hold a woman’s body at their center, and that take into account the way a woman understands her body by and through its losses and living history.

I would place Dingman’s Through a Small Ghost alongside Monica Youn’s Blackacre and Pimone Triplett’s Rumour for how powerfully and tenderly it handles the subjects of (in)fertility, miscarriage and child loss, as well as for how it invents the particular forms and grammar it needs; there is a violence at the heart of life that each of these poetry collections deftly acknowledges. In Dingman’s book, I notice particularly the way the verb “hang” appears, as in the lines, “she folds herself into a crane / to hang from the ceiling / of someone else’s womb,” or in “Matrimony as Indefensible Human Experiment”:

What if I say no. Just this once.

We have died with the birds & weather

& winter. We have died with the sky

& stars that lie as they hang themselves

against the night. What if I say it’s okay.

That there is violence in even the early miscarriage, and that a person’s body can feel the loss as such, is a lived reality that Dingman’s collection blows open with the force of a gale’s wind. I mention earlier my unpreparedness as a reader for Dingman’s work, but in truth I was not prepared to have my readerly resistance to a collection broaching painful topics completely turned on its head—Dingman’s Through a Small Ghost has helped me think through a miscarriage, two births and difficult postpartum periods. This is no small thing, that Dingman has the language and the heart for transforming how we are able to think and imagine women’s narratives—our own narratives as women—and that Through a Small Ghost gives us some of the missing pages from the emotional-physical story of women’s bodies. To close with Dingman’s words: “the body // is a story of devotion: it knows the cost of moving / into morning, asking to be spared // nothing.”

wifthing by Pattie McCarthy. Apogee Press, 2021. 96 pages. $18.95.

Susan Howe writes of Pattie McCarthy’s wifthing: “Through threads and threats of mothering history the intercession of love pardoned and restored with fury and reverence.” Wifthing, a collection of “80 unpunctuated sonnets,” traverses the histories of medieval and early modern women (mystics, queens, goodwives of Salem) through the Middle and Old English language of “wifthing” and “wif,” with three groups of sonnets falling under the subtitles “margerykempething,” “qweyne wifthing,” and “goodwifthing.” Margery Kempe, considered to have dictated the first autobiography in the English language (The Book of Margery Kempe), features prominently. Kempe was known for her weeping and wailing in church, her desire and negotiations for a chaste marriage after bearing more than a dozen children, her public preaching and her pilgrimages to holy sites. In McCarthy’s poetry, the reader meets Kempe in all her contradictory glory:

not getting any closer to the offing

margery kempe gives birth in a hairshirt

a wifthing par excellence a female patience

figure in her fourteenth confinement

…

in lieu of education margery

kempe learns her prayers by heart & by rote

& maybe she mums them while chained

up in a stockroom in her postpartum

The sonnet is a small room—like looking through a window into a miniature scene—where McCarthy can both delimit—often through repeating, circling lines—the figure of Margery Kempe, mother and mystic, physically restrained after birth to prevent harm from postpartum psychosis. The hairshirt—the discomfort of holy persons—is tangible sign of a chosen holiness in Kempe’s life, a striving-after a pilgrim’s life despite the many constraints of her own. The first sonnet concludes “your daughterthing is sound / asleep your little / girl in sound,” offering a resting moment at the poem’s close that could reference Kempe’s child, or the speaker’s, or both. The possible slippage should awaken readers to the fragility that is still maternal and natal health, and to the fact that sometimes a sonnet’s form can hold a mother and child more soundly than modern medicine.

McCarthy brings a warmth to the language of “thing” that might threaten objectification to modern readers—instead, “thing” opens to the language of creatureliness. One “margerykempething” sonnet opens “the boys take their fighting into the barn / the pigeons take their omens down the chimney / this creature drinks coffee on the porch / a weather eye out & ears on the barn.” The boys, the pigeons, the coffee drinking creature become animals together in the world, rather than apart or in separate categories of being. This particular sonnet is one considering perception, and the speaker wonders at physical and linguistic “double movements” evidenced by “a sparrow in the grass,” causing them to remember words applied to Kempe: petty, neurotic, vain, illiterate, mental banality. “Heresy in the eye of the beheld,” the sonnet ends (Kempe was accused of heresy and tried several times). McCarthy strikingly employs repetition—the language itself underscoring and performing the repetitions of a life. Here are two examples:

margery kempe gives birth & gives birth & gives

birth & gives birth & gives birth & gives birth &

gives birth & gives birth & gives birth & gives birth

& gives birth & gives birth & gives birth & gives

birth

Words on the page represent Kempe’s fourteen labors—totaling more than four lines of births, more than a quarter of a sonnet. How do we measure a woman’s life? How do we weight it in a sonnet? The next sonnet opens:

margery kempe is brought in for questioning

& is arrested & is arrested

& is arrested & is arrested

& is arrested & is arrested

& is arrested & it’s a lucky

creature escaped the fire

It is interesting to me how the content of Margery Kempe’s life fills the sonnets—the fourteen children she (possibly) did not want to have, the arrests for public preaching and heresy—as though a different life would change the sonnets, so carefully do they record. On the other hand, McCarthy’s sonnets show how a society can write the sonnets of a person’s life, and can dictate certain lines—but not all of them. Not even when lines wither to single words of accusation:

you

are

no

goodwife

Some say biography does not matter when reading poetry and literature—in fact, some readers act like biography can be distained, and that the reading can somehow be “purified” by not considering biography. But what about the creative work that is born out of—and bears—biography? I will never forget having a conversation with another woman poet about women’s writing and gendered (in)visibility—“a man looks humble if he doesn’t talk about his own work,” she said, “a woman disappears.” There is always an element of recovery when writing about women’s lives, even when it’s about as exceptional a woman and historical figure as Margery Kempe, one of the most famous medieval women and well known across multiple fields.¹ Combining collaged language, life events and Middle English (“thu lyest falsly in pleyn Englysch”) alongside glimpses of the speaker’s own biography makes rich life-scapes of the sonnet’s form—a form known for its logical patterning and argument as much as its rhyme schemes. Because of the physical limit of a sonnet—the size of a human palm, that is all—sonnets are language-scapes in a way other poetry forms are not, and McCarthy makes great use of the form’s minor—and totalizing—tensions: “margery kempe invents the autobi- / ography & vernacular tell-all” begins one sonnet and another: “you are the shape of my midlife crises / margery kempe,” and another: “your grammar has driven me outdoors.” In her series and sequences of sonnets, McCarthy finds the formal engine to hold multiple biographies, even while Margery Kempe is finding her own narrative’s form: “margery kempe told her book to her son / but it was neithyr good englysch ne dewch.”

Whereas the spoken word (also in the forms of trials and interrogation) fills the “margerykempthing” sonnets, in the sequence of “qweyne wifthing” sonnets, speech acts turn towards the bearing of children itself. The first sonnets notes:

her complete education included

a fair hand hawking being daughterthing

to kings & wedding kings & giving birth

naturally to king as well

The transition to sonnets for women who were also queens alters the power dynamic—or does it? The subject is still women, the power ultimately in another’s hands—rather, I think, McCarthys work shows the reader how power relationships are integral in the form of the sonnet itself, to the tensions that warp and woof the palm-sized text. The line “she / makes her body by making other bodies” is an ars poetica for a woman poet employing the sonnet form at the same time as it is a description of a medieval queen’s job description. The layers of power over a woman’s body come more fully into view in the second “qweyne wifthing” sonnet: “margaret when I fuck you I am fucking / all of anjou all of england deep in france.” The lack of capitalization throughout McCarthy’s sonnets comes more fully into play in the “qweyne wifthing” sonnets, as countries are lowercased alongside proper names, as the language assumes both vernacular voice and informal presentation on the page. Lines like those directly quoted above are startling to read, and underscore how much formality we are willing to ascribe to sonnets as a form translated and taken up by seventeenth-century male poets of the English courts.

There is an abundance of topics I am not reaching in this review—from iambics to middle English verbs, to the appearance of first-person plural in several key sonnets, to the goodwives/“witches” of Salem—but I want to close with lines that, for me, illustrate the (powerfully tender) facility McCarthy brings to her time and space and language-travelling sonnets, and to the leaking and uncontainable phenomenon that is still women’s writing:

I called out sick to write this poem

I turned on paw patrol to write this poem

I look to the whale-path to write this poem

I squint into the yellow angle to write

this poem I speak it into your mouth

I shift my winterbody to write this

poem I write it like parallel play

¹ There is a reason that, 11th hour, I decided to not write my dissertation on John Milton’s poetry and prose, but on four women poets contemporary with John Milton, and non-household names: Mary Sidney Herbert, Amelia Lanier, Katherine Phillips and Mary, Lady Chudleigh