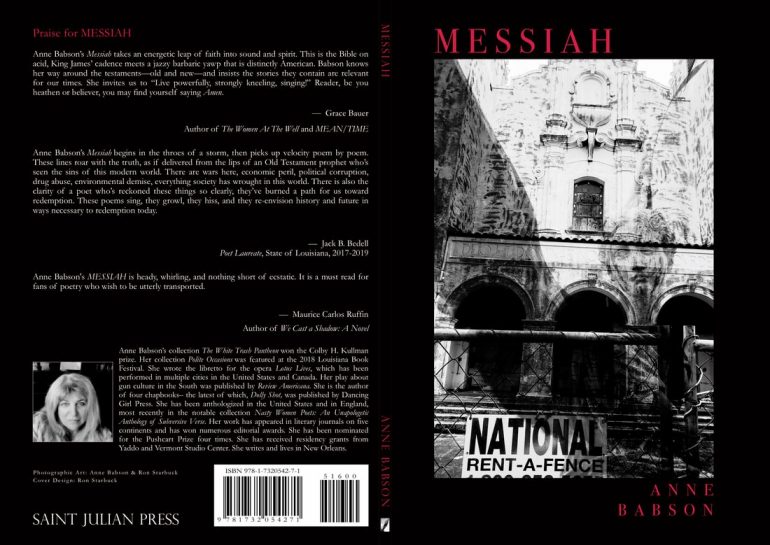

Our Interview Editor Esteban Rodríguez talks with poet Anne Babson about the power of faith and poetry, honest depictions of American landscapes, and her most recent collection Messiah (Saint Julian Press, 2019).

Can you tell us a little about your book and how your most recent collection Messiah (Saint Julian’s Press, 2019) came to be.

I got the idea for Messiah for several reasons. I was miraculously healed by faith of all symptoms of a genetic blood disease, one that promised to significantly compromise my health for the rest of my life. I felt extraordinary gratitude for that miracle and still do. I acknowledged to myself how much I wanted to thank God in my work as a poet.

At the time shortly after that healing experience, a friend of mine took me to Lincoln Center for a do-it-yourself singalong of Handel’s Messiah singalong. Avery Fisher Hall Orchestra played, and they had paid professional singers as soloists. The rest of us took parts in the larger chorus, the whole concert hall did. Afterwards, we left the hall and sang traditional American Christmas carols in four-part harmony around the Lincoln Center fountain, and it was lovely!

I started to think about how to set sacred art poems in the American landscape, about what an American DIY Messiah oratorio might look like on the page. I realized that it would need to follow the diverse metrical structures of American music, talk about the environment of this country, possibly as a metaphor for our own psychological and spiritual pollution and redemption, and it would have to give us the hope of the Gospel, the Good News that God loves us and forgives us. But I didn’t want it to sound “churchy,” as anyone who has either engaged in evangelism or has been approached by someone on the street with a Bible tract knows, saying “Jesus” fifty times fast doesn’t communicate in an era rife with hypocrites the radical love of Christ for even the least of us. How might I communicate how radical and delightful the message of the coming, birth, death, resurrection, and second coming of Jesus is? I realized I could approximate holy mysteries more with epithets rather than the name of Jesus itself. I call him things in the collection like “Our Magnificent Stuntman.”

But I wasn’t talking about “God, the Universe, or whatever.” I was talking from a very theologically orthodox perspective on Jesus, trying to reach an audience who would be unlikely to accept a Bible tract on the street. I therefore structured the book with the same Bible passages that inspired Handel’s songs, and I retained in large measure the titles of those songs as I turned to America, our land, and our music.

I also write as a woman wrestling with the patriarchal traditions surrounding the person of the Virgin Mary. I have written a number of poems that wrestle with women and religion.

I got a grant from Yaddo to work on the very beginning draft of these poems. I added and polished many more of them over the course of more than a decade.

There are landscapes in Messiah, specifically American cities, that are vividly described, sometimes not in the best of light. In “New Orleans Quintet,” we see New Orleans in disarray:

I saw my city sliding in sludge.

Cockroaches cowered in corners and courts.

Bridges and barges bore barnacled bludgeons.

Shotguns and shipyards shared circuit shorts.

And in “Every Valley Shall Be Exalted,” a microscope is taken to New Jersey and its not-so flattering features:

New Jersey, your comatose cul-de-sacs

will be exalted!

Your monoxide-spewing Turnpike

will snake crooked!

Your rubber–tire strewn marshlands

will blossom exalted!

Yes, your toxic waste dumps

will rise green, exalted!

Basement apartments in Camden,

rented through crooked

Real Estate with no repairs

will turn penthouse, exalted!

Can you speak about how you approached depictions of city landscapes that outsiders might not experience or see daily, and why these places evoke such inspiration.

One of the Hebrew names for God is Ha Makom, or “The Place”. I have always found this intriguing—the thought that God is geographical. The entire book examines our relationship to a God in situ, and all ancient peoples considered a blighted landscape as a sign of disfavor from the divine. In our own traditions of the United Sates, the spiritual has been intimately linked in our discourse with the geographical. Note that the Puritans talked about coming here to found a community that would be a shining city on a hill, and Jefferson’s words in the Declaration of Independence declaring our freedom refers to “nature and nature’s God.” For Jefferson, to find America’s God, one examines America’s nature. In it, per Jefferson, we find that we are free and endowed with inalienable rights. So, if I were going to write a DIY American Messiah, I was going to write it in American dirt.

The Bible talks about both divine and worldly cities a great deal. Abraham has to leave (lech lech’a) the city to speak to God in the wilderness. So, it seems, did the Jews in Exodus. But Jerusalem itself is a place of divine appointment for Christ, and in the Bible, there is both a Heavenly Jerusalem, and an Earthly Jerusalem. The name in Hebrew, Yerusala’im literally means “Jerusalems,” and in medieval art, it is often depicted as a double-consciousness-endowed topos, often with a city hovering above in the sky directly over a city on Earth. Jesus weeps over earthly Jerusalem, but Heavenly Jerusalem descends to meet him as a bride in Revelation.

I am not certain it is possible to fully understand the God of the Bible without understanding cities. I begin the whole book with an Epigraph from Isaiah 66:6—”A voice of noise from the city, a voice from the temple, a voice of the LORD that rendereth recompence to his enemies.” I chose that verse because I think it embodies the tone I have striven to give the collection.

I also have passages set in more rural settings as well, but because the Bible talks so often about cities, it seemed fitting to talk about them in this work. Furthermore, I am a city dweller. I imagine that a number of the readers of Ecotheo are more engaged with rustic settings, find God’s presence in a redwood grove rather than Times Square, but I know cities and understand them. My favorite thing about New York City where I lived most of my life was that on any street corner in a busy section of town, I could close my eyes for a split second and hear perhaps 200 languages being spoken around me. That noise to me was prayerful, almost like all of us together, saying like Samuel, “Speak, LORD.”

I have endeavored in Messiah to include somehow the voice of the multitudes of us in America. I find them most easily in urban places.

As with cityscapes, the body is at times not seen positively, at least in the sense that it is devoid of the spiritual connection it longs for. “Thus Saith The Lord (Transposed for Soprano)” exemplifies this sentiment:

Where? “and I will fill this house with glory.” Which house? cathedrals? Or the synagogues? Which house? My house? Could it be my body, This torso, the temple of the living God? She thought of her breasts in a white light flood. The sermon moved on. The prophesy stood.

Can you elaborate on how you decided to write about the body and what you hope it conveys throughout the collection.

I am particularly interested in the female body in this collection, given its complicated relationship to Christianity. How does one understand holiness in a body that is sexualized by society so often? I found that the feminine relationship to the divine had to preoccupy my own thoughts as both a believer and as a writer. I wrote about it in the poem you mention and in others.

Your collection contains a variety of poetic forms, including sonnets, ghazals, and poems with interesting and intricate rhymes and line patterns (“His Yoke is Easy” is a linguistic labyrinth, an interesting labyrinth that’s worth reading a few times). To what extent did the subject matter drive the form of these poems, and vice versa.

The work of this book as a whole is, among other things, a commentary on the diversity of American music, so I wanted to make the book feel like it was singing to the reader. I found formalism both nonce and conventional, gave the feeling of song. Some of the poems in this book were actually recorded for a holy hip-hop CD called The Cornerstone, which was quite an honor for me, as professors don’t generally end up recording in record studios in the Bronx.

As to the driving factor of form or substance, when I began to make the poems “sing” to the reader, I don’t believe I compromised meaning for form but rather listened attentively to Handel’s Messiah Oratorio’s meter and repetition and made something more modern happen that captured a sense of rhapsodic joy.

What has the reception to your book been thus far, and do you feel that it is interacting with the world the way you envisioned when you began putting pen to paper?

I have been asked to read these works in such diverse places and have been well-received there that I have to believe these poems manage to communicate hope to very different groups of people. I have been (unsurprisingly) invited to read in churches and at Christian colleges. I have also been invited to read these poems (and read again) at a New York drag bar, on a hip-hop CD, and at many other places. They have been (prior to the release in November of the book) published in journals as conservative as Bible Advocate and as liberal as a socialist anthology in England. I hope that this is because I am communicating how much God loves all of us. I think that we ought to try to remember that daily.

How have faith and love of God shaped you as a poet? Are there other moments, apart from the one above that lead to Messiah’s genesis, that stand out in your career as defining?

I may think more than other believers do about how God created the universe with words.

I remember a trip my family took to England when I was five years old. I had an aptitude for reading already, but it was in no way up to reading The King James Version of the Bible. Nevertheless, after our plane ride, my parents and little brother passed out with jet lag in the hotel, and only I was awake. The only thing I could do in that hotel room was read, but any picture book that might have been packed for me was deep inside a suitcase I was too small to open. I opened a drawer and pulled out the “Placed here by the Gideons” KJV and sat on the cool tiles of the bathroom and began to read. I did not understand much of anything, but I was struck by the majesty of the language of Genesis. I imagined God making the planet with His words. I did not understand much about what went wrong with Adam and Eve, except that they knew it was wrong to be naked outside (I think I may have gotten in trouble for that once at that age) and that God punished them. By the time that God was chiding Cain: “thy brother’s blood crieth unto me from the ground” I shut the book because I thought it was spooky that the blood could cry, and I got scared. I did not touch the Bible again until much later in my life—I got saved at 23— but I remembered how majestic a God would be who could create everything by using language. I knew the most powerful thing I might ever learn to do was to gain mastery of words.

As for a career-defining moment as a poet, I think that, too, happened when I was about that age. At age six, one of my great uncles gave me a beautifully illustrated book of children’s poetry, one which included Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Mermaid.” Like so many other little girls, I loved mermaids, and so I read it aloud. In the second verse of the poem, Tennyson describes a mermaid combing her hair:

I would comb my hair till my ringlets would fall

Low adown, low adown,

From under my starry sea-bud crown

Low adown and around….

I became utterly fascinated with this passage. I did not have the vocabulary to describe what Tennyson was doing, but I understood that “low adown” was an onomatopoeic construction to give both the gesture and even the sound of a woman with long, thick hair running a metal comb through her tresses. I read that passage over and over again, and I knew I wanted to learn how to make people see unseen things using words and their sounds.

I know that these two experiences made me yearn to write poetry. I think that any aspiring poet must truly apprentice himself or herself to great words written by others. The first part of the poet’s career is that of hyperattentive reader. Only after inhaling great words may one exhale great words, and that with great labor and difficulty. And continual attention at that level to new words remains a hallmark of any poet who wishes to innovate in what Gertrude Stein called “late language.”

If you could describe your poetic journey in a few words, what would they be?

I am on Whitman’s open road, and all of America is before me, waiting to be discussed. I am the workmanship (paema), a creation of the One who created the universe with words, who is Himself the Word made flesh. I am at the crossroads of old, dusty books and the vernacular of the streets. I hear music. I dance. I dance on the page.

What’s your best advice to younger poet, and what advice would you give your younger self?

Read everything you can, but read like an apprentice magician learning to steal the tricks of the magic show of the great masters. Be disciplined with your work. To write, as Camus admonished, is to rewrite, so polish these words of yours like gemstones. Be bold in your first drafts. Be mercilessly exacting of perfection in later drafts. Then read some more.

Fear not. Believe only.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]