Judgment springs up like hemlock in the furrows of the field

– Hosea 10:4

Save Our Hemlocks! Save Kentucky’s Hemlocks! Save Georgia’s Hemlocks! Pages like these are sprouting up on the internet from agencies and groups dedicated to “saving hemlocks.” When most semi-educated folks hear the word “hemlock,” the first things they say are “Isn’t that what killed Socrates?” and “Why would we want to save them?” If the plant used to kill Socrates was in trouble, we probably wouldn’t want to save them, but not because we want vengeance for his untimely demise. Socrates was probably poisoned by Conium maculatum, a weedy plant known throughout the Old World as a pretty nasty poison. This was likely the plant referred to by Hosea because, like all good weeds, it does spring up in fields and roadsides after soil disturbance. In Eurasia where it is native it might not be that aggressive (although it can’t be that great for farmers or Hosea wouldn’t have called it out), but in the U.S. it is an extremely aggressive noxious weed that was introduced to our shores as an ornamental plant decades ago and spread like, well, a weed. We’ll talk more about invasive plants in a future column, but just bear in mind that quite a few of the species that we’ve spread willy-nilly all over the globe have wreaked havoc on their new habitats (see the last column for the effects of nonnative rats on native small mammals for an example).

So now that we’ve established what we aren’t trying to save, what are we trying to save? The Eastern hemlock, Tsuga canadensis, is an evergreen tree native to North America that has nothing whatsoever to do with poison hemlock, other than early settlers saw some vague resemblance and called it that. Our hemlock is a pretty big tree found in moist forests, generally along rivers and creeks in the Appalachians from North Georgia up into Canada, and is considered a keystone species in the coves where it dominates. As the most common evergreen in its habitat it provides needed shade on the creeks all year round – without these big shady hemlocks, many (if not all) of these creeks would be under direct sun for a lot of the year and their temperatures would rise a few degrees. That might not sound like much to you, but then again you aren’t an endangered fish like the blackside dace which is barely surviving as it is in the hemlock coves of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. To a dace, along with several other rare fish and dozens of plants, salamanders, and other species, the shady, moist creek or creek bed is the only home they have – it’s pretty impossible for many of these species to adapt to the rapid changes in temperature and cover that come with the loss of hemlock forests. And some of these hemlock forests are pretty impressive both aesthetically and spiritually. One of the sites that personally make me feel close to God’s creation is in Letcher County, Kentucky, at a place called Bad Branch Nature Preserve. I must not be the only one to feel that way, because the trail meanders along the creek through an area known as the “Hemlock Cathedral.”

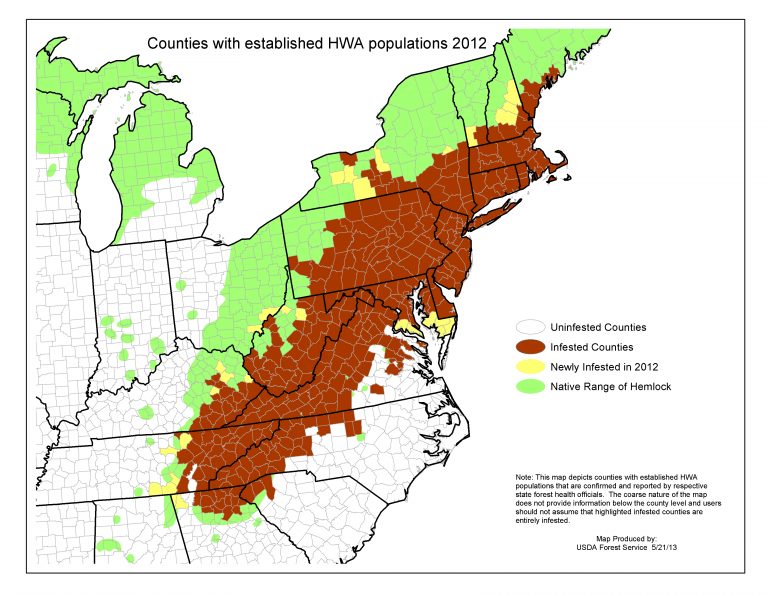

So now that we know which hemlock we are trying to save, why does it need saving? Along with poison hemlocks humans have spread thousands of other pests outside their native range, including one teeny little insect that only kills Eastern and Carolina hemlock trees, the Hemlock woolly adelgid, or “HWA.” And it kills them with extreme prejudice – in the last decade it has killed hundreds of thousands of trees in the central and southern Appalachians at an alarming rate. Once a cove is infested with HWA, those trees have a couple of years left and then they are goners. In the summer the insects are virtually invisible and can hitch rides on birds or hikers pretty much undetected – this is the “crawler” stage. If the bird or backpack or boots they are hanging onto takes them to another hemlock cove—which can be pretty easy to do in the Smokies, or Appalachian Trail, or just about any of our forest areas in the Eastern half of North America—they drop off at the nearest hemlock tree and go to work. In the winter they form fuzzy, cotton ball-like masses on the tree branches, hence the “woolly” in “woolly adelgid.” In the spring they wake up and commence to killing the tree once more. After all the hemlocks in the area are dead (and I do mean all as mortality is pretty much 100%) the HWA either die as due to lack of food or hitch a ride to the next cove. They leave countless acres of dead hemlocks behind—which can mean unstable stream banks, creeks baking in the sun that have been in the shade for perhaps millennia, plants and critters that evolved to live in moist shady areas left high and dry, and a perfect opportunity for invasive plants to, well, invade, just like those other hemlocks in the furrows. Forest ecologists liken the effects of HWA to chestnut blight, which wiped out one of the most dominant hardwood species in North America in the early 1900s. Doom and gloom!

Fortunately, there are a few things that we can do to help out these hemlock woods before they are all gone. There are a couple of pesticides that will kill the HWA, but they have to be applied to each tree individually and are only effective for three to five years – a pretty expensive and labor intensive process in remote Appalachian forests located with extremely steep slopes. This is where you come in. Most of the “Save the Hemlocks” groups are focused on chemically treating hemlocks in significant natural areas, like Bad Branch’s hemlock cathedral. And they need your help. Although in most states only licensed pesticide applicators can use these chemicals, a lot of work is needed up front to measure and mark the trees before pesticides are applied. One extra person can make this work move a whole lot faster and save a lot more trees before they die, much less a church group. If you aren’t crazy about chemicals, you should know that the US Forest Service is also breeding beetles that eat HWA in hopes to have enough to release in very remote areas (we’ll discuss the controversy about spreading “biological control agents” another time).

The most important thing for you to do is something. Starting is as simple as a Google search of “save the hemlocks” for a particular state, or a call to the US Forest Service at 828-257-4314 asking who is working on the problem in your area. Whether you live near the Eastern US from Maine to Georgia or just love the Appalachian Trail or the Great Smokies, a day or two of work in the woods can save a small ecosystem. Saving the hemlocks means saving the salamanders and fish and orchids. And keeping those other hemlocks in the fields where they belong.