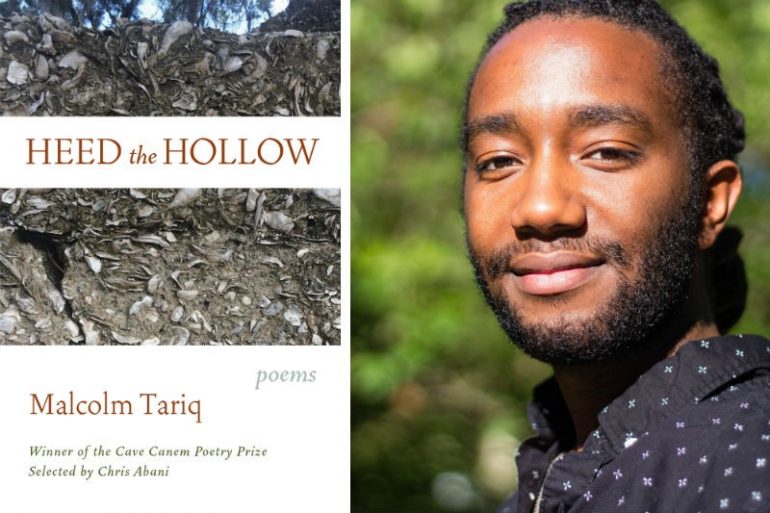

The initial idea for Heed the Hollow came after I left the South. I had moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan for graduate school, and on a visit home to Savannah, Georgia I came across a cement-like material with oyster shells mixed in it. I had grown up seeing this regularly, but only now living outside of Coastal Georgia did I realize I’d never seen it anywhere else. I discovered that this was called tabby, a type of concrete made of oyster shell, water, lime, sand, and ash that was used as a substitute for bricks in the Coastal Southeast in the Colonial period. The labor-intensive process heavily depended on slave labor.

Heed the Hollow started with two end poems and developed as a project with me attempting to connect the two. I used HD’s Trilogy as a model to write “Tabby,” a long poem of couplets involving myth, the grotesque, Southern memorials, and the legacy of slavery. Then in the summer of 2016, I went to the Cave Canem retreat where I wrote a poem called “Power Bottom” about accessing queer desire and sexual control after having grown up being taught not to accept that part of me. I asked myself: How does the act of bottoming inform my own subject position as a Black Southerner? Does desire and sex have anything to do with the ways we create historical narratives? And, more importantly, what if Southern Studies was centered on Black queerness?

In the initial stages of writing Heed the Hollow, I completed a different manuscript that was sent to several first book contests. Thankfully, that project was not published, though it did come close. Once I had the blueprint for this second manuscript, I submitted it more selectively to maybe four or five places. I was excited when I got the phone call that it was selected for the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, but I was also worried that the book did not feel complete to me. That fall, I moved to New York City and spent five months vigorously writing and editing before I submitted the final manuscript to my editor. Part of this process was getting feedback from readers I trusted, which happened one Sunday evening over wine and food in my windowless Brooklyn living room with about eight friends.

This is the one-year anniversary of that manuscript workshop and I’ve been thinking about how I see the poems living outside of my original vision. I consider Heed the Hollow to be a Southern project, but it is also more specifically a Black southern project. Even so, as one of the initial poems reminds readers, it is rooted in a Black Queer Southern Studies. As such, while it’s true that I’m writing for so many readers within that matrix, I am really only thinking about the welfare of my people when I write. When I create, I’m thinking about my contribution to that invention of the future that Black people are and have been building collectively. I am wondering what we will say about the South next.

The book’s cover is a photo of tabby that was taken on a research trip to Sapelo Island, just off the coast of Georgia. My younger brother ended up accompanying me and my friend that day, and another option I submitted for the cover was a photo of his hand reaching through a window of a tabby slave cabin. I like this photo because it features my brother, who is essentially from a different generation than me. And more featuring the past and the present, it indicates that reach toward a future to which I always aim to write.