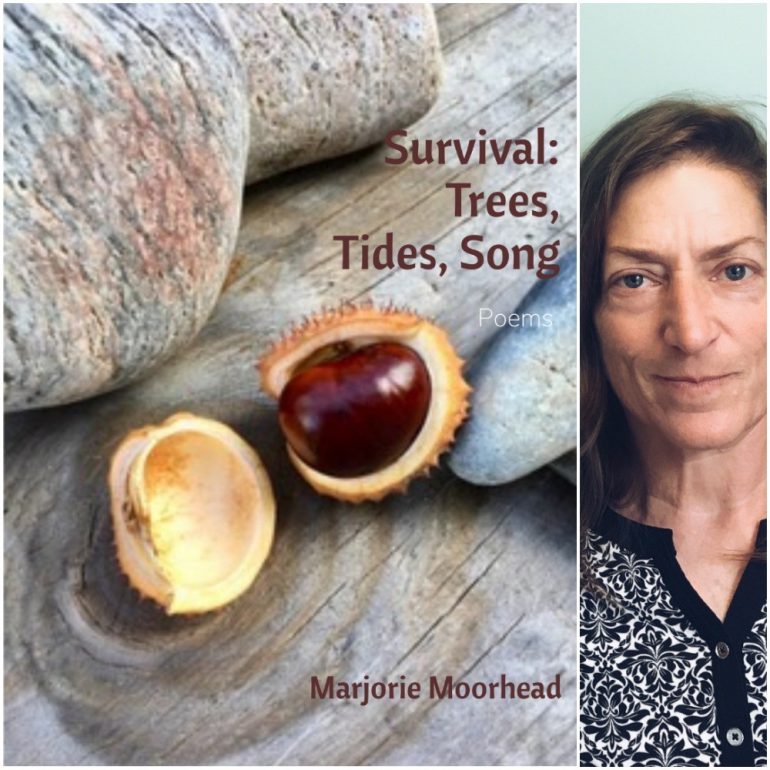

“Seems the only thing saving me / these days is trees,” writes Marjorie Moorhead in her debut chapbook Survival: Trees, Tides, Song (FLP, 2019). The poem continues:

The fact of trees. How they are; their particular presence. Saves me from separating into parts. Bits that could float apart or burst outward at some seam. Bolting off in opposite directions away from center; from core.

The linking of confession with nature’s presence (and nature’s repair) echoes what Emerson wrote of trees in his essay “Nature”: “In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life—no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes) which nature cannot repair.” Moorhead and Emerson both write about the woods and trees as a unique place of spiritual repair—articulating for me that consolation I feel in my local park, walking a paved loop that circles through sycamores, oaks, sweetgums and loblolly pine. Since the 1980s, doctors in Japan (and, following, the U.S.) have prescribed Shinrin-yoku, or “forest bathing,” as a therapeutic practice for their patients. It seems the medical sciences—and the poets long before—are onto something. In Moorhead’s poem “Join Me,” the trees rise as a meditative image before the poem’s speaker, their physical presence evoking the language of “presence,” “center,” and “core.” If Emerson finds that “all mean egotism vanishes” in the woods, Moorhead’s speaker finds both herself and others there, and the poem is one of invitation rather than solo rhapsody.

Trees are not the only saving presence in Survival: Trees, Tides, Song—in “Starlight in My Pocket,” comfort is a stone: “I keep a rock from the beach in my pocket. / Smooth, to rub. Silky soft surface. / Dissipates worry,” while the poem “East Thetford, VT” opens with the tercet:

Walking saved me years ago Walking the same route every day Day after day season after season.

Within the poem, Moorhead embeds small catalogs of observation from the walker’s physical day: “Early morning; mid-day; dusk,” “Grasses; corn; clouds,” “Smells; wind; birds,” and “Dirt; puddles; tracks.” The poem calls the reader in, to experience the ordinary day—the walking motion of the body, the surrounding earth and farming landscape. “East Thetford, VT,” and other poems in Survival, affirms aspects of Andrew Epstein’s critical text Attention Equals Life: The Pursuit of the Everyday in Contemporary Poetry and Culture. Epstein writes:

…[the] invigorated poetics of the everyday arises in response to the crises of attention roiling contemporary culture. Everyday-life poetry attends to, and in some cases decries, the very rhythms, practices, and structures of daily life that our sped-up, addled culture threatens to obscure. For example, it forces us to think about the ways in which power and capitalism shape and affect tiny details of everyday life, the micropolitics of daily interaction and economic inequality, the realities of everyday sexism and racism, the effects of consumerism and advertising on our minds and actions, and the existence of alienation in the day-to-day workplace.

Moorhead’s poetry acts as an antidote to “the crises of attention” by pulling back to a slow and singing observation, by resisting being overwhelmed by a busy world. Her speaker literally notes: “My steps, my thoughts; / the rhythm of stride, breath. / Watching and noting details. What changes; what stays constant.” “East Thetford, VT” reminds us that attention paid to our daily steps is not lost on the self’s spirit, or the self’s sense of place in the world: “Relationship with land can be just a road / claimed with each footstep. / You know it, because you walk it.” The poem advocates not for consumerism, not for ownership, but for a moving presence and relationship through repetition. The final, listing line of the poem offers the mantra: “Repetition; observation; devotion.”

There is a linking, too, between dailiness and simplicity in Moorhead’s poetry—a striving for clarity that echoes Jane Kenyon, Rae Armantrout, Mary Oliver, A.R. Ammons. The poem “Thank You Mary Oliver” opens, “You say them so well; so clearly; / Simple and holy things.” The idea that the simple and the holy are related to each other, and that our attention to simple things holds the quality of holiness (and a means of surviving), runs throughout Survival: Trees, Tides, Song. In “Turtle Island Microfiber,” the speaker listens to the radio and hears of “particles of plastic in Lake Champlain / so small, they can’t be filtered by treatment plants. / ‘Micro plastic trash’ they called it.” A few lines later, the speaker listens to her son “visiting home from college,” “my head spinning / trying to keep up with all his words for environmental and social tragedy.” What, the poem asks, happens to the physical world when our language for describing and observing it changes? The speaker wonders:

Apparently, we are trying to repossess ourselves of our humanity away from psycho technology in the Anthropocene.

The shift into technical language shows a difference in linguistic registers between the speaker and her son, but also the speaker’s acknowledgement that caring for the world—in this poem, the micro plastic pollution in Lake Champlain and Turtle Island—is a shared, intergenerational project, despite the different lexicons we use.

One way language is joined and related in the chapbook is through Moorhead’s frequent use of semicolons as she lists, observes, and builds—often with (and through) a gathering effect. For example, in her poem “Surviving,” the speaker notes, “We all need to rebuild; / restructure. Mend and improve. / The process must be inclusive; respectful; dedicated.” The semicolon makes a claim for grammatical connectivity in Moorhead’s work and the sharedness of her project. In “Tides,” the speaker asks a question with a semicolon: “Is there Balance; Justice in our universe?” Here, the semicolon divides and joins both halves of the poetic line, suggesting that, for all life in the Anthropocene, it is one, joined question of survival. The two-stanza poem divides and inverts itself, repeating its first stanza’s lines, with variation, in its second: “Each wave brings in a crop of sand. / For inspection: bits of shell, glass, wood, shimmering scales; / remnants of a below-the-surface sea-ruled world at hand.” The earth repeats itself and its questions, the poem’s form proposes, if we listen to it, watch it, feel it with our feet and our hands.

May we all be as attentive and as open-hearted as the speaker in Marjorie Moorhead’s Survival: Trees, Tides, Song. May we listen to each other, and the differences of our language, and respond. In the final words of the poem “Join Me”:

Let’s stand with trees to gather; collect.