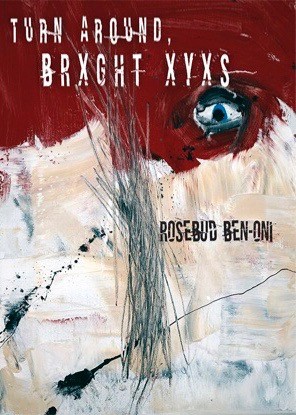

A conversation and peer review of Rosebud Ben-Oni’s turn around, BRXGHT XYXS (Get Fresh Books, 2019) by Tom Snarsky and Jo Ianni.

TS: In her interview here at EcoTheo, Rosebud Ben-Oni mentions an emotional valence that feels stuck to the roof of my mouth as I type this: a “kind of in between melodramatic-serious joy-sadness.” I love this moment in the interview because a) who hasn’t negotiated that kind of feeling? and b) it hints, in its hyphenation, at one of the ways her poems see the world, and even the way we’re going to try to do this review: through the complexifying lens of quantum superposition, where two elements are not dialectically forced to be one, but instead they are brought into a kind of higher-order being, where each is just as real as the other and only an act of determination can make us choose only one eventuality. In the time since assembling turn around, BRXGHT XYXS, Rosebud has written many poems that interact with the complex realism mandated by contemporary interpretations of quantum physics, and like good quantum realists I think we can reverse the arrow of time a little and play with retconning some of those ideas into this book. I like the idea of superposition as putting the “+” in bi+, like when we read these lines from “Even Doves Have Pride” about Ben-Oni’s ex: “Don’t put me in a poem, she said, then read [/] One meant for another [/] And thanked me.” There’s such complexity here!

JI: This is exactly the kind of, forgive me, “magic” that struggling with reality in, or with, quantum terms makes possible. It’s worth thinking about this in tandem with the ballad form which appears as a topic of discussion in the same interview you’ve mentioned, and figures not only in the title but throughout the book. In fact, as I’m responding, I’m listening to Bonnie Tyler and thinking how could you avoid retconning quantum interpretations to a lyric like “Forever’s gonna start tonight.” The song proves a great guide for moving through these poems “holding” through any error and the dark. This holding that Ben-Oni’s poems have to do over and over, overlapping the differing conversations and subject matters they tackle. It’s not a fully formed thought at this time, but what happens to the ballad’s I when subject to a quantum poetics? Is it too cheap for me to ask if “every now and then I fall apart”? I want to believe that the I of these poems is asking something like this question.

TS: Yes!!! I love the moment in “She Calls Once That Is A Lie” where—I don’t think it’s an over-exaggeration to say—the I does fall apart:

When she calls in the morning I’ve changed my number address identifying features I’ve sacrificed my name when she calls in the morning

That last line is just so good it makes you want to stow it away in the whorl of a big old tree for rainy days. Anyway, one thing I think the ballad form does really well is it takes even the most shambolic I and, by giving it a rhythm, allows it to persist and perdure even when the forces of passion or desire are all but ready to smash it to pieces. The rhythm, for instance, of lines like Rosebud’s “All the wild beasts I have been [/] Are ripping me apart again.” I think one kind of poem that really leaves an impression on me is the kind that pushes back so hard against the speaker’s unity of voice that the poem actually coming out in one voice sounds like a miracle.

JI: Reading through I find myself feeling the same. All these disparate topics that “the voice” of Ben-Oni’s poems stumble through really puts pressure on the very notion of a unified voice in the text but, I think another interpretation is possible as well. While Ben-Oni’s poems might have a unity of voice, which is not necessary, that voice tumbles with a sort of bravado or reckless courage, at times, even excitement, through differing timbres and perhaps different temporalities. I’m thinking of a poem by e.e. cummings where the final line is “listen: there’s a hell [/] of a good universe next door; let’s go.” I see this gesture exemplified again and again in these poems, and firstly so in “Dancing with Kiko on the Moon” where the use of brackets, superscript and hyphen or subtraction amplify this possibility–not to mention Ben-Oni’s use of the page’s physical space. Sometimes the poems will start left justified but then sprawl and fall and constellate across the white space. It’s really easy to find yourself, if not with purpose, then, by accident reading lines in concert that may not have been intended to be read together. Although, I admit, I’m the kind of reader who invites that kind of chaos with an ardor.

TS: I love those cummings lines! I also love the kind of universe-jumping you’re describing, and I think there’s a connection between that and the way that love is always a way forward in these poems: to quote “I Guess We’ll Have to Be Secretly in Love with Each Other & Leave It at That,” “To love as resistance but not always [//] the way back.” Love is exactly this “chaos with an ardor” you’re talking about, the motivic force that moves the speaker through her countless touchstones of music, pop culture, friends, romances, and all else. The way that same poem ends shows, I think, three amazing things: that love gives us hope, that love contains even the most disparate terms (and joins even ostensibly separate universes), and that love is even a way to understand home:

To having hope

in our pop-up whit of the world,

its edges sour & peeling,

To never really having left jerusalem

which is why I’m still busted stars

& throwing elbows.

To the hours we made horses between nightfall

& war. To should go home. To leaving it

the longest way

of derailed horsecry

& amaranthine bones.

JI: I think what makes this “universe-jumping” possible is the sense of space, the way the poems appear formally and physically. The above example is perfect in the way it slithers or vibrates or forms a rivulet. I can’t help but focus in on “derailed horsecry” to further my point. (I admit my fascination with concrete poetics in this interpretation.) I think Ben-Oni has this rare quality of considering the movement of an eye as it reads across a page, giving credence to a material-spatial relationship extending between the body of work, the writer’s poem, and the body of the reader, the reader’s eye. I want to suggest this for a moment, in collaboration with your point, as a kind of gesture towards love. That love between the writer and reader by means of the text where these poems form a distance or place for love to be requited or even unrequited, where the possibility to say “I love this!” emphatically is permissible.

I am thinking of Joshua Beckman’s essay “On Books” in his recent collection of essays when he thinks of the book’s porousness as a means for people to be friendly who couldn’t possibly be friends. Maybe we could extend that with Ben-Oni’s poems being a way for people to love who can’t for one reason or another. This connects to the ballad form as well. I can’t tell you how many stories I have or times I have personally experienced someone singing maybe a Queen song for instance who would have nothing to do with the real life Freddie Mercury. Now, I want to stress that Ben-Oni does something special and peculiar with these formed spaces. Inside them are gaps, ticks and pauses that suggest such a love, if we can call it that, can endure more uncertainty and friction. These places of confluence can still be full of love but also contestation.

TS: Yes! That last piece, the contestation, is a beautiful name for what I think of as these poems’ braggadocio, the Chelsey-Minnis-(gurl)esque bravado of certain of Ben-Oni’s lyrics:

So send in the pink ladies No the spice girls no drown me in the pool and darling I’ll undivine the dolphin within every showgirl Cause when you leave I’ll destroy your memory with a face smothered in cold cream

Like, wow.

You once told me that a certain poet we both fail to admire wasn’t a bad poet, per se, but that they were a bad dancer. Ben-Oni could step up to the barre and teach us all a thing or two.

JI: I was prepared to pull out my go-to Pope line, “True ease in writing comes from art, not chance, / As those move easiest who have learn’d to dance.” But I’ve been reading Renee Gladman’s Calamities, and hopefully I’m permitted to borrow a line from her which I feel describes these poems better, “swirling underneath like broken dances.”

***

In the spirit of the crucial pervasiveness of music in Ben-Oni’s book, here are some important (albeit asynchronous) listens for our reviewers as they had the foregoing conversation:

TS: Jackson C. Frank’s late albums, “The Book of Love” by the Magnetic Fields, “Silver Dagger” by Joan Baez, “Death with Dignity” by Sufjan Stevens, ANOHNI’s Paradise EP and her song “I Never Stopped Loving You,” “Napoleon Solo” by At the Drive-In, random DSBM Spotify playlists.

JI: Bon Iver’s album i,i, “I Want You” by Savage Garden, “I Fall Apart” by Post Malone, “Holy Terrain” by FKA Twigs featuring Future, Don Caballero’s album For Respect, Hella’s album Hold Your Horse Is, Yowie’s album Synchromysticism, Dilly Dally’s “I Feel Free,” Calvin Harris’s “Slide” featuring Frank Ocean, “Oh S**t!!!” and “What’s Goodie (feat. Cakes da Killa)” by Injury Reserver, “A Stone is a Stone” by Helena Deland and “Purifier” by The Building, to name a few…