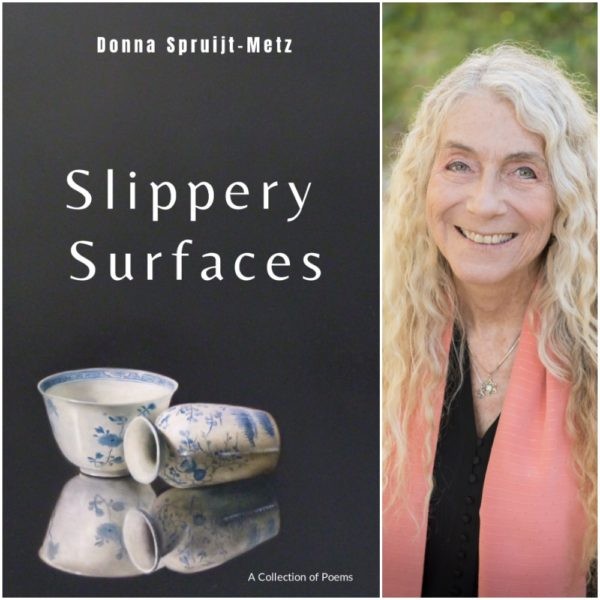

The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote that human experience of the home is a primarily imaginative experience and that by dwelling in a place, our imagination constructs meanings and memories that become integral to the home. Dwelling is thus a form of lived experience, and we use these memories of our lived spaces to understand and approach the world. To Bachelard, we draw upon memories of our childhood homes and younger years as a map, and “cover the universe with drawings we have lived.” This phenomenological approach is central to the writings of Donna Spruijt-Metz, whose first chapbook, Slippery Surfaces, was released recently by Finishing Line Press. A collection of poems that converse and illuminate meaning within each other, Slippery Surfaces touches on the effect of parental neglect on a child, and how it lingers on after the child has become an adult.

Spruijt-Metz opens Slippery Surfaces with the poem “Ponytail.” The poem’s tone is understated, beginning with a rhetorical question “Remember Patti Playpal?” that situates the memory in the realm of childhood. Details follow: the speaker’s younger self is being taken by her mother on a plane journey, a discussion on how long it takes to fly from Los Angeles to Honolulu. However, “Ponytail” takes a darker turn, as the speaker reveals that her father has recently died. As she does so, she maintains a tone of detachment, allowing no insight into the emotional states of either mother and daughter. In its place, Spruijt-Metz invites readers to meditate upon the way the bodies of mother and daughter inhabit their shared bed: “there was hardly room / for the two of us.” Rather than providing a satisfying conclusion, the poem’s mother-daughter relationship remains slippery and open to interpretation.

While a risky strategy, for the lack of payoff may discourage casual readers from reading further, it is evident that Spruijt-Metz’s ambiguity serves a broader goal of interrogating memory. In this sense Spruijt-Metz is a collaborative writer, whose trust in her readers allows her to envision grand collages of memory. Readers are encouraged to draw connections between events, and each poem is informed by details that came before. The image of the mother and daughter, unable to fit comfortably together in “Ponytail,” informs the image of the child speaker in the poem “Under the Piano,” where she “crawl[s] unnoticed” to observe her mother singing to party guests. Spruijt-Metz’s deft use of space suggests an emotional distance between mother and daughter, implying that her younger self was not welcome into the spaces that her mother occupied.

A significant number of poems in Slippery Surface focus on the speaker’s mother, a figure portrayed as inscrutable and difficult to understand. A number of poems make a valiant attempt at probing her emotional depths: “Dendrochronology for My Mother” transforms the rings on the speaker’s mother’s hands into tree rings, generating a comparison of the human body in non-human terms (in dendrochronology, tree rings can be studied to find out climate conditions of the past). Spruijt-Metz’s poetry does the same, examining the mother’s rings in order to speculate about her past:

This ring tells me of fine wild sex and these of music. Narrow as a witch hunt ill-omened as a name, these tell of age—

Still, these comparisons only go so far. The final stanza of the poem steps into the realm of the religious. Examining a final ring – hinted to be a wedding band – Spruijt-Metz’s poetry invokes seraphim (“six-winged spirits”), angelic beings whose biblical references are found in the visions of the prophet Isaiah. In Isaiah’s retelling of heaven, a seraph presses a live coal to Isaiah’s lips, cleansing him of sin and guilt. In Spruijt-Metz’s poetry, however, the live coal does not cleanse sin, but seals the mouth from further speech. The poem ends on a frustrated note, highlighting that her mother’s silence belies a deeper narrative.

Spruijt-Metz’s quest to understand the speaker’s mother appears as a sequence of poems titled “Daughter and Mother, Amsterdam, Tram 4.” Spruijt-Metz uses an extended tram journey as context for a conversation between the speaker and her mother. A geographical terrain rich with symbolic power, it is possible to understand the tram line as a proxy for how the conversation progresses towards and away from the truth:

Stadhouderskade

Frederiksplein

Did you ever miss him?

Prinsengracht

No, I was too angry.

Keizersgracht

Rembrandtplein

Spui

How did he really die?

Dam

Centraal Station

Dam

In this poetic sequence, Spruijt-Metz is as much a phenomenologist as she is a poet, creating a dynamic interplay between the active mind and its surroundings. Her use of tram stops adds a dramatic quality, conveying the hesitations and pauses in conversation between mother and daughter. Additionally, her speaker’s question of how her father died resonates with the location that the tram has stopped at: Spui, a tram station built on reclaimed land, was originally a body of water that formed the southern limit of the city until the 1420s, when the Singel canal was dug as an outer moat around the city. Just as the city’s growing population and trade demanded an expansion of the city’s bounds, the daughter’s desire for the truth demands an answer from an unwilling mother. The poem’s reading cannot be extricated from the setting, and Amsterdam is essential as a landscape to the poem’s excavation of truth. While Bachelard may have focused his seminal work on the notion of the childhood home and its spaces, Spruijt-Metz’s scope is broader—considering the city itself as a space holding insight into a mother’s actions.

A strength of Slippery Surfaces is its ability to use the poetic sequence mentioned as a dramatic scaffold to influence our readings of other poems. Where it succeeds, poems gain greater depth, drawn into the narrative between Spruijt-Metz and her parents. Consider “School me,” a poem by Spruijt-Metz that references Psalm 25, a penitential psalm. Psalm 25 expresses King David’s desire for God as well as his plea for mercy and deliverance from his enemies. Often used as a devotional psalm to explore a person’s relationship with God, and how a sense of unworthiness is often the cause of spiritual loneliness, the narrative of Psalms 25 is referenced by Spruijt-Metz’s poem to approach the subject of shame felt by the persona. Written in italics, hinting that the voice of the poem is not Spruijt-Metz’s own, “Call me” tenderly evokes the feelings of shame and isolation that the persona feels. The persona makes a plea for God to accept their flawed nature, lingering on the image of God and man seated together (“Here, I made this nest full / of half truths […] It would be good / to wait / together”). Coming just two poems after the second of four poems in the poetic sequence, wherein it was revealed that speaker’s mother had sought a divorce after finding out her husband had cheated on her, “School me” appears to represent the feelings of shame and loneliness that the speaker’s father experienced following the emotional fallout. While it is within bounds to interpret the poem as separate from the unfolding narrative, the loose order that structures Slippery Surfaces compels readers to treat Spruijt-Metz’s poems as a constellation of smaller narratives that can combine into a greater whole.

Towards the end of Slippery Surfaces, Spruijt-Metz reckons with the memories that have been raised through her chapbook. What does it mean to have never had a normal childhood? If Bachelard’s theory of the home is considered: we continuously draw upon our childhood to interpret the world. A lack of a stable childhood would thus negatively impact how one approaches life as an adult. Spruijt-Metz frames this psychological knock-on effect through the natural world in the poem “The Web Teaches the Spider.” In it, she draws a loose analogy between a human and a spider, suggesting that just as a spider can learn to fish for prey after having its web cut, humans possess the capacity to adapt after loss. However, this adaptation is not positive, but deadly:

Where receptors are missing, a part of the world ceases to exist. Thus, the arm knows how to move the arm the hand knows how to shoot the gun.

With her use of enjambment, Spruijt-Metz lends emphasis and intensity to her conclusions. A loss of stability leads to the inability to conceive the world in certain ways, the lingering on the word “cessation” being paralleled by the image of gun suicide in the closing stanza.

The collection remains uneasy as it turns to examine the speaker’s relationship with her daughter. A professor of psychology and preventative medicine, Spruijt-Metz is cognizant of the possibility that a similar dysfunctional relationship may yet replicate itself; when the speaker sees her daughter in the poem “Fifteen,” she is haunted by her relationship with her mother. However, the closing poem, “My husband bought me a mirror” invokes a sense of self-reflection. Including a detail about the mirror’s magnification, Spruijt-Metz suggests that the power that narratives hold are determined by how much we over-examine and over-fixate on them. Her speaker asks herself, “Now, am I a woman with a / rusty narrative?” With characteristic ambiguity, the poem offers no conclusive answer. Yet, it is possible that in such ambiguity, an answer has already been found.