Growing up, some of my most cherished memories took place on Grandpa Dwight’s farm. The farm was his retirement project, his attempt to cultivate thirty acres of land that otherwise would have gone neglected. Located about an hour north of Seattle alongside the edge of the Puget Sound, the farm was not simply a place for growing crops, but also a place for growing relationships, among church communities and larger families. Us grandkids had the distinct honor of being “insiders” to his retirement project as he would train us how to use the equipment that was required to pull it off: whether that be the gardening implements, the shop tools or the various tractors.

As children, we of course thought it was the coolest to use all this stuff. But as I got older I began to realize what made this farm so successful was not simply how well Grandpa took care of the land, but also how well he took care of the equipment. This was especially important in light of the fact that the Pacific Northwest rains would subject many of the tools to rust and rot. In fact, many of the tools in his possession were from the various auctions he would frequent, where the previous owners had not taken such good care of their equipment. And so Grandpa acquired used and imperfect equipment at the perfect price.

(With a mix of nostalgia and frustration, I can remember the hay baler that only tied half of each bale, meaning the other half of each bale had to be carefully handled and manually tied. But one day, Grandpa found the replacement part needed for the baler. The “old” hay baler became more than sufficient to bale the hay on his land; in fact, his neighbors would often ask him for help baling their own hay.)

I believe the lesson I learned from my grandfather, that one must take care of the tools in order to take care of the land, has major implications for thinking about more abstract environmental challenges such as climate change. In the context of this election cycle, I cannot help but think we need to start thinking about how we are taking care of what is perhaps the most useful tool for addressing climate change: our democracy.

Stewardship

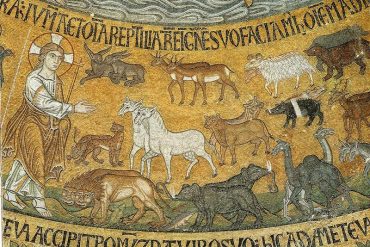

Let me start from the beginning of the train of thought that has led me to this point. As a Steering Committee member for Young Evangelicals for Climate Action (Y.E.C.A.), a movement of young Christians in the United States demanding that our political and faith leaders address climate change, I spend a lot of time discussing stewardship. It is this word we have rallied around in order to advocate for a biblical ethic of taking care of God’s creation that God (in his infinite and baffling wisdom) has entrusted to us mere humans. In his book The Nature of Environmental Stewardship, Johnny Lin defines stewardship as:

Relative to the environment, the vocation of humanity is as a steward of creation. A steward manages the property of the owner; a steward is a temporary caretaker. This management, however, is marked by care and service. Stewards have a relationship not only to the owner but also with those for whom the resources are intended as well as the personal needs of the steward. Stewards also have an obligation to steward the things they have been given in accordance with the wishes of the owner, and stewards are judged on whether they earn a return for the owner. Stewards do, however, exercise some level of autonomy; they are creative and have real responsibility.

Because we spend a lot of time thinking about climate change, we at Y.E.C.A. spend a lot of time thinking about our democracy. Collective action is necessary to address a collective problem like climate change. While individuals can take personal action to minimize their carbon footprint, ultimately what we need is for everyone to change their behavior. For that to happen we need the economic systems—those utilized to purchase, sell, move, remain, live, dream, and decide—to be reimagined and transformed.

In the United States, securing such collective action requires democratic participation. Opposed to more authoritative, top-down methods of securing climate action, democracy guarantees that the burdens (and opportunities!) associated with addressing climate change will be distributed fairly. Democracy is our best chance to make sure collective action on climate represents not merely a technical victory, but an actual moral victory.

But, like the equipment on my grandfather’s farm, our democracy has to be taken care of. In other words, in order to be stewards of God’s creation, we have to become stewards of our democracy.

Stewardship’s Arch-Nemesis

In America, the 2016 presidential election cycle has been fascinating at best, frustrating at worst, and baffling to everyone. It is temptingly easy to explain the sins of the other side, but how do we explain the idiosyncrasies of our own? Everyone and their uncle has shared commentary on this election, and to the pile of speculation allow me to add one more.

I wonder if it our democracy has fallen prey to stewardship’s arch-nemesis: consumerism. That is, the worldview which values creation only for the moments of acquisition and consumption. Simultaneously ideological and pathological, consumerism blinds us to the hard work that sustains creation and makes us complacent about waste and pollution.

All the symptoms of consumerism are apparent in our election culture. We are told to be “informed voters” and so we choose our elected officials based off of television advertisements, or celebrity endorsements, or trusted reviews in the media. In the primaries, political parties resemble free markets where an entrepreneurial candidate can easily disrupt the entire system, simply by appealing to some untapped sentiment held by the electorate. When running for office, politicians must contort themselves into brands, so that we can know them through their campaign logos and slogans and merchandise (don’t forget, the breakout star of this election cycle was a brand long before he was a politician). In democracy eroded by consumerism, we are stuck imagining that the only way to be politically engaged is by voting, perhaps because ballots resemble order forms: pieces of paper on which we mark what we want and expect to receive.

Stewardship is the proper response for how we should approach anything that we receive as a gift and one day will give away. Democracy seems to fall under that category, being a product of history more than something that can be simply willed into existence. I might even daresay that democracy, where it exists, is a gift from God, just like anything else that exists despite the prevailing opinion that the world is doomed to hostility, despair and emptiness. At the very least, our democracy certainly is not something you or I built, but rather something we were born into and can hope to pass on the next generation.

You Are Destined To Have An Effect

My friend Grant is a middle school English teacher, whom I respect for his ability to integrate social justice lessons into the curriculum. When I talking about these ideas regarding climate change and democracy with him, Grant pointed out to me another way how climate change and democracy are related. By living in a world where either climate change or democracy are realities, you are destined to have an effect on the world around you, whether you choose to or not. Even inaction is some form of action; everyone has some degree of responsibility.

Participating in the movement to address climate change has given me hope for democracy. I think about the Paris Agreement, the international climate treaty that was negotiated late last year. Usually when all the countries of the world get together to try and some to a solution about a collective governance issue like climate change, the outcome is rather disappointing. This does not seem to have been what happened in Paris: when the final gavel struck, the whole assembly erupted in cheers and applause and even some tears and hugs.

What was different? Perhaps it was the fact that over the past decade or so, there has been a shift in reimagining climate change not simply as a technical problem but as a moral issue. If so, the success of the Paris Agreement reflects the continued growth and persistence of the climate movement.

Democracies are sustained by movements. Sure, there are various institutions that we often recognize as being a key part of democracy: voting rights, citizenship, parties, legislatures, etc. But these institutions, as necessary as they are, are fallen and inevitably become corrupt over time. Institutions need movements in order to stay centered on purpose.

As a Christian who has been involved in the climate movement as a faith-based activist and organizer, I cannot help but think how crucial a role the church has in this process. Personally, I see churches as places that give birth to movements. These movements are complex and sometimes even dialectical (see, for example, “conservative” and “progressive” Christians). But it is my belief that these movements are movements that matter, movements that are not oriented toward destruction but rather are creative movements, creative because they are oriented towards the God who is Creator.

What Success Looks Like to a Steward

The first Y.E.C.A. event I ever attended was a prayer rally outside the 2012 Presidential Debate at Hofstra University in New York. I had only learned about Y.E.C.A. a couple of weeks earlier, and quickly agreed to make the flight only a couple days earlier. My job was to find one of the Steering Committee members who would also be there, and then stake out a spot for the larger crew coming via caravan from Washington DC. Of course, none of these people, besides the organizer whom I had grabbed lunch with, would be people that I had met before.

The closer I got to Hofstra, the thicker the atmosphere filled with the democratic concentration that surrounds high-profile political events. Campaign banners and government choppers filled the air, while media vans and activist groups filled the streets. It was a bit of a carnival, with people wearing pink or blue or white or black or whatever color their cause required. Creativity points went to the guy dressed up as Bane from that summer’s blockbuster The Dark Knight Rises, a not-so-subtle allusion to candidate Mitt Romney’s time as a venture capitalist with Bain Capital (if you go through my profile pictures on Facebook, you’ll find a photo of me fist bumping with Bain Capital, while in the background there are some Orthodox Jews protesting American complacency regarding the occupation of Palestine).

I found Katie, the Steering Committee member, bunkered down in a Baskin-Robbins near campus. As Katie and I waited for the group to arrive, we swapped stories and got to know each other. One of her high school friends was one of my college friends, we found out. We were spotted by the only other climate change “group” that was there, a charismatic woman and an enthusiastic man and their polar bear puppet that together made up the “Pissed Off Polar Bears”. The mainstream environmental groups had decided to sit this one out, too afraid to shake things up for the incumbent, leaving us non-partisan evangelicals alone to find solidarity with the climate movement’s dramatic fringe (although, I must confess, they were quite friendly).

The caravan arrived just before sunset. Nearly two dozen evangelical Christians poured out, each wearing Y.E.C.A.’s signature orange T-shirt. I met for the first time many of the people who I would later call colleagues and friends, shaking hands and exchanging names and finally getting a T-shirt of my own.

There was an “open mic” stage for groups like ours; we used our time slot to make a short statement, offered a prayer for God’s creation, and then sang Amazing Grace. We then walked on over to a lecture hall where we could watch a broadcast of the debate that was happening right next door, and after the debate concluded we gathered together for a private time of reflection and prayer and fellowship.

Did we accomplish anything that evening? The cynics would say no: Superstorm Sandy’s trip to New York a few weeks later did exponentially much more to put climate change on the radar of the 2012 Presidential election than our own convergence in New York City; neither did climate change seem to be a make-or-break issue for any down-ballot candidate. But I think these people are missing the point; they are stuck on a “consumerism” view of democracy that only measures engagement by its immediately visible returns.

From the “stewardship” view, I think our gathering was an unqualified success. I measure this by relationships built, convictions expressed, sacrifices made, and political processes engaged – all indications that suggest we made our democracy a stronger tool for addressing the challenge of climate change.

I take as evidence the shift in media coverage we received immediately after the Hofstra event and in the years to come: a few days later, a local news blogger called us some “evangelical hippies”; a few months later, I found myself one of many among the Y.E.C.A. leadership being interviewed by This American Life (sadly, the tape never aired); about a year later the snarky environmental news-magazine Grist.org mentioned us for the first time in a column titled “Is there Hope in the World?”; that next summer we were featured in a front-page story in The New York Times; and, finally, late last year our National Spokesperson was quoted at the top of an Associated Press story about a new poll about religious American’s environmental attitudes – and no explanation of who we were or what we stood for was necessary. Long story short: in-between election cycles, we had gone from being obscure and ironic to becoming a trusted authority on evangelical Christianity and climate change. We had raised the level of discourse, in terms of optimism, charity, and nuance.

Stewarding Tools, Stewarding Land

Today, I have the privilege of leading Y.E.C.A.’s conversation as we discern how we want to relate to this roller-coaster of an election cycle. For me, the theme that keeps coming to mind is that lesson I learned on my grandfather’s farm: that is, stewarding the tools is part of stewarding the land. Democracy is one of the best tools we currently have for addressing climate change; if we want to steward God’s creation we need to remember to also steward our democracy.

My prayer, therefore, is that we seek purity. I speak not of purity within particular policies or programs, but rather in our relationships to each other. Although we might have to get our hands dirty in a messy election cycle, we can remember that if Christ’s blood can wash away our sins, then it certainly can wash away the incidental grease that comes along with keeping our democracy in good shape. May we have the courage to leave our consumerism-imposed comfort zones, and may God find us faithful to the calling of stewardship.

If you’re interested in learning more about Y.E.C.A. and finding out how you can get involved visit http://www.yecaction.org/sign_the_petition

A similar version of this essay appeared on Shared Justice.